I very much enjoyed Neil McMillan’s witty and creative plenary on the last day of the IATEFL Edinburgh Conference (McMillan, 2025), in which he lamented the lack of interest in methodology in recent IATEFL plenaries and made a convincing case for task-based language teaching (hereafter TBLT). I shared his shock that a key icon in the IATEFL community, Jane Willis, has never delivered such a plenary and recall how transformative her 1996 book was for me in my own career, being a fledgling teacher at the time (Willis, 1996). What follows is in no way a criticism of TBLT itself, but is rather a critique of frequent misunderstandings of it as (sole) best practice methodology and the dangers of bias in a research community – something that is certainly not applicable only to TBLT!

In Neil’s plenary, as part of his argument for the efficacy of TBLT, he cited a systematic review by Bryfonski and McKay (2019), a study that other proponents of stronger versions of TBLT (e.g., Jordan & Gray, 2019) have also cited in support for their persistent arguments over the last 30 years or so that it is superior to other approaches within the broader communicative language teaching movement. The Bryfonski and McKay (2019) meta-analysis is deeply problematic, and a very good example of why meta-analysis isn’t always reliable (see, e.g., Glass, 2000, the originator of the approach), nor necessarily the best way to understand the impact and transferability of specific phenomena in the highly complex field of education – something I know from having published systematic reviews myself (Anderson & Taner, 2023) and contributed to the literature on systematic review/research synthesis methodology (Anderson, 2024a).

What Bryfonski and McKay’s study actually reveals

Bryfonski and McKay’s study has been widely criticised, not only by other researchers of TBLT (e.g., Harris & Leeming, 2021), but even by the original authors themselves (see Boers, Bryfonski, Faez and McKay, 2021). This later, more critically astute article reveals that almost all of the studies that Bryfonski and McKay included in their original meta-analysis in fact constituted examples of task-supported language teaching (Boers et al., 2021, p. 11), in which “tasks are simply methodological devices for practising specific structures” (Ellis, 2019, p. 455), essentially as a more communicative version of PPP (presentation-practice-production; see Anderson, 2016), rather than the stronger form of task-based teaching that Mike Long and Geoff Jordan have long argued is the only form that can be effective based on what they perceive to be appropriate and sufficient evidence (e.g., Long, 2015). Ironically, therefore, the first point to note here is that the strong effect size (d = 0.93) of the Bryfonski and McKay study (2019) actually provides compelling evidence for task-supported language teaching, something that I have always argued can also work effectively (see e.g., Anderson, 2020; Ellis, 2020), and is also supported by some (not all) high quality studies over TBLT (e.g., Li et al.’s (2016), randomised controlled trial (the gold standard in experimental research) which is strangely absent from Bryfonski & McKay’s (2009) meta-analysis, even though they cite it, raising further questions about their inclusion and exclusion criteria).

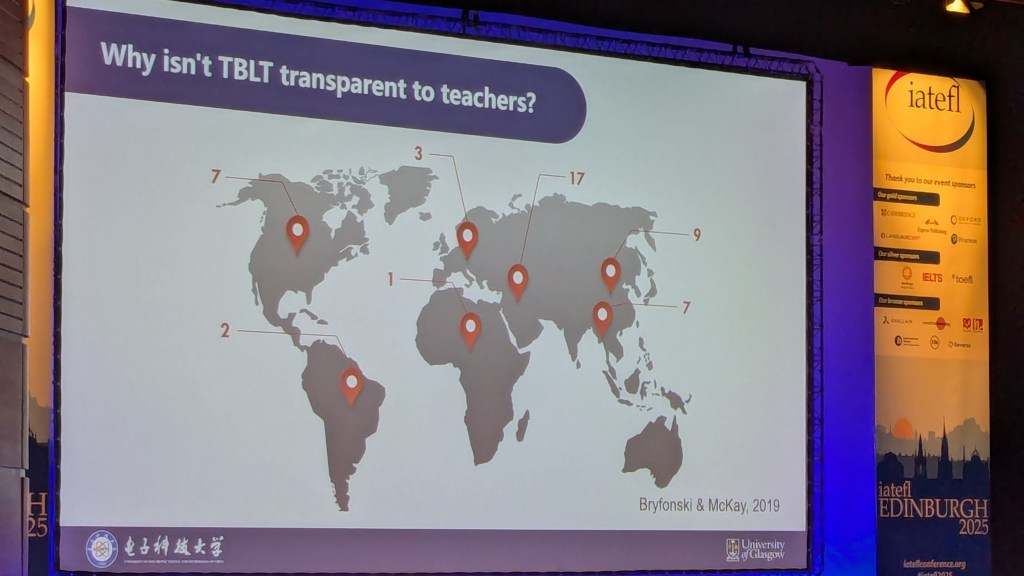

By the time Boers et al. (2020) systematically removed all of the studies from Bryfonski and McKay (2019) that either did not involve TBLT or are problematic in other ways, they actually found a negative impact of TBLT: “an averaged d-value of -0.06” (Boers et al., 2020, p. 15)! It’s important to state that this is not evidence that TBLT isn’t effective – the sample size is too small. Nonetheless, the fact that the original study ever got published, and has since been cited over 170 times (Google Scholar stats) offers clear evidence of systematic bias, and arguably critical illiteracy, both within the academic peer-review community (the original study was published in Language Teaching Research, for which the double-blind peer review process should have identified these multiple, significant shortcomings) and among those that have since cited it as evidence for stronger forms of TBLT without first assessing it critically, including Geoff Jordan and Neil McMillan. It is indeed ironic that the very study that they have cited in support of their arguments actually constitutes evidence against their arguments. As Neil points out in his talk, Bryfonski and McKay’s (2019) synthesis included research from a wide range of contexts worldwide (see Figure 1), and while Boers et al. (2020) offer important critiques of some of these studies, the meta-analysis itself nonetheless provides evidence that tasks can fit into synthetic curricula and work well in diverse contexts worldwide, and also, importantly, that it’s OK and effective for those teachers who prefer to, or are compelled to, work within the constraints of such curricula to do so, contrary to Long and Jordan’s repeated arguments against such practices.

Towards methodological ecosystems, not monocultures

I share Neil McMillan’s passion for methodology in language teaching – it is a continuing fascination of mine (e.g., Anderson, 2014, 2019, 2021) – as well as his concern that it has often being sidelined in applied linguistics research nowadays. But it’s important to remember that there are important reasons why ELT and educational linguistics discourse has largely moved on from attempts to identify and implement a universal best practice methodology – language classrooms are today about so much more than the narrowly-defined psychocognitive process of competence acquisition that earlier SLA research tended to focus on (see Anderson, 2024b) and which in turn shaped stronger models of TBLT. Indeed, as Prabhu (the originator of TBLT) himself came to recognise, “there is no best method” that can fit all contexts (Prabhu, 1990, p. 161). We have moved on to what is sometimes called a post-method era, in which we recognise the need to understand numerous other important factors as important influences and affordances for how we conduct teaching and learning in our highly diverse language classrooms around the world (see Hall, 2025; Kumaravadivelu, 1994, 2001, 2006). This doesn’t mean that method isn’t important, but underlines the fact that we need to approach method itself from the perspective of critical curiosity, sensitivity to context and a spirit of inclusion and understanding – recognising the need to see methodology itself as part of the ecosystem (including those methods that we hold dearest). This contrasts markedly with the alarming “theory culling” (Long, 1993, p. 225) that Mike Long tried, but failed, to carry out, and which prompted the sociocultural turn in applied linguistics (see Block, 2003; Firth and Wagner, 1997, 2007). This turn, most of us acknowledge, has made us so much stronger and wiser as a community in ELT and educational linguistics. As ecologists remind us, diversity itself is a key indicator of a healthy ecosystem (Costanza & Mageau, 1999).

References

Anderson, J. (2014). Speaking Games. Photocopiable Activities to Make Language Learning Fun. Delta Publishing/Ernst Klett Sprachen.

Anderson, J. (2016). Why practice makes perfect sense: The past, present and future potential of the PPP paradigm in language teacher education. English Language Teaching Education and Development, 19(1), 14-22. http://www.elted.net/uploads/7/3/1/6/7316005/3_vol.19_anderson.pdf

Anderson, J. (2019). Activities for Cooperative Learning: Making Groupwork and Pairwork Effective in the ELT Classroom. Delta Publishing/Ernst Klett Sprachen.

Anderson, J. (2020). The TATE model: A curriculum design framework for language teaching. ELT Journal, 74(2), 175-184. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/ccaa005

Anderson, J. (2021). A framework for project-based learning in TESOL. Modern English Teacher, 30(2), 45-49.

Anderson, J. (2024a). Metasummary: examining the potential of a methodologically inclusive approach for conducting systematic reviews of educational research. Educational Review. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131911.2024.2401079

Anderson, J. (2024b). Reimagining educational linguistics: A post-competence perspective. Educational Linguistics, 3(2), 258-285. https://doi.org/10.1515/eduling-2023-0009

Anderson, J., & Taner, G. (2023). Building the expert teacher prototype: A metasummary of teacher expertise studies in primary and secondary education. Educational Research Review, 38, 1-18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2022.100485

Boers, F., Bryfonski, L., Faez, F., & McKay, T. (2021). A call for cautious interpretation of meta-analytic reviews. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 43(1), 2-24. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0272263120000327

Block, D. (2003). The social turn in second language acquisition. Edinburgh University Press.

Bryfonski, L., & McKay, T. H. (2019). TBLT implementation and evaluation: A meta-analysis. Language Teaching Research, 23(5), 603-632. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362168817744389

Costanza, R., & Mageau, M. (1999). What is a healthy ecosystem?. Aquatic ecology, 33, 105-115. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1009930313242

Ellis, R. (2019). Towards a modular language curriculum for using tasks. Language Teaching Research, 23(4), 454-475. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362168818765315

Ellis, R. (2020). In defence of a modular curriculum for tasks. ELT journal, 74(2), 185-194. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/ccaa015

Firth, A., & Wagner, J. (1997). On discourse, communication, and (some) fundamental concepts in SLA research. The Modern Language Journal, 81(3), 285-300. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4781.1997.tb05480.x

Firth, A., & Wagner, J. (2007). Second/foreign language learning as a social accomplishment: Elaborations on a reconceptualized SLA. The Modern Language Journal, 91(S1), 800-819. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4781.2007.00670.x

Glass, G. V. (2000). Meta-analysis at 25 (unpublished manuscript). Downloaded (06/07/2021) from https://www.gvglass.info/papers/meta25.html

Hall, G. (2024). Method and Postmethod in Language Teaching. Routledge.

Harris, J., & Leeming, P. (2022). The impact of teaching approach on growth in L2 proficiency and self-efficacy: A longitudinal classroom-based study of TBLT and PPP. Journal of Second Language Studies, 5(1), 114-143. https://doi.org/10.1075/jsls.20014.har

Jordan, G., & Gray, H. (2019). We need to talk about coursebooks. ELT Journal, 73(4), 438-446. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/ccz038

Kumaravadivelu, B. (1994). The postmethod condition:(E)merging strategies for second/foreign language teaching. TESOL Quarterly, 28(1), 27-48.

Kumaravadivelu, B. (2001). Toward a postmethod pedagogy. TESOL Quarterly, 35(4). 537-560. https://doi.org/10.2307/3588427

Kumaravadivelu, B. (2006). Understanding language teaching: From method to postmethod. Routledge.

Li, S., Ellis, R., & Zhu, Y. (2016). Task-based versus task-supported language instruction: An experimental study. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0267190515000069

Long, M. H. (1993). Assessment strategies for second language acquisition theories. Applied Linguistics, 14(3), 225-249. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/14.3.225

Long, M. (2015). Second language acquisition and task-based language teaching. Wiley Blackwell.

McMillan, N. (2025, April 8-11). Big tasks and uphold tasks: Making a case for TBLT [Conference presentation]. IATEFL Edinburgh 2025, Edinburgh, United Kingdom.

Prabhu, N. S. (1990). There is no best method—Why?. TESOL Quarterly, 24(2), 161-176. https://doi.org/10.2307/3586897

Willis, J. (1996). A framework for task-based learning. Longman.

Dear Jason,

Lovely to meet you in Edinburgh IATEFL!

What a compelling reflection! Thank you for this thoughtful critique.

Your analysis of the Bryfonski and McKay (2019) study is particularly eye-opening. I appreciate how clearly you unpack the methodological concerns and show how interpretations of “effectiveness” can be easily skewed without close critical engagement. It is a timely reminder of the importance of research literacy, especially when meta-analyses are often taken at face value.

I really like your call for methodological ecosystems rather than monocultures. It is refreshing to see such a grounded argument for embracing complexity and contextual sensitivity in pedagogy, rather than chasing one-size-fits-all solutions. Prabhu’s “no best method” stance still feels very relevant, especially in today’s increasingly diverse and dynamic classrooms.

I like your heartfelt appeal for pluralism and open-mindedness. A very welcome voice in the ongoing conversation.

Have a lovely weekend!

With very best wishes,

Chang

LikeLiked by 1 person

There’s a serious point in here about the need to revisit the Bryfonski and McKay (2019) article and to recognise that it doesn’t provide the suporting evidence that it claims to for the pedagogic efficacy of courses which implement a strong version of TBLT.

There are also a number of other points made in this blog post which are false, fallacious and purile. For example, while expressing shock at those who failed to check the assertions in the Bryfonski & McKay article, you confidently claim that Jordan & Gray have “persistently” argued “over the last 30 years or so” that a strong version of TBLT is “superior to other approaches within the broader communicative language teaching movement”. Had you taken the trouble to check your assertions as carefully as you expect others to check theirs, you would know that Humphry Gray is twenty four years old and has never argued the view you attribute to him. In my case, I’ve argued the merits of a strong TBLT approach for approx. 10 years, but you’re wrong to say that I’ve persistently argued, that it’s “superior” to other approaches “within the broader communicative language teaching movement”. I don’t know what the broader communicative language community refers to and I’ve never used the word “superior” to describe any approach to ELT.

I’ll put a full reply to your post on my blog, soon.

LikeLike

You misquote me. I state that “other proponents of stronger versions of TBLT (e.g., Jordan & Gray, 2019) have also cited in support for their persistent arguments over the last 30 years or so that it is superior to other approaches within the broader communicative language teaching movement” – I’m here citing YOUR article with YOU as lead author. Academic literature is part of scholarly discourse and open for critique, something you’re particularly keen on, I recall. The ethical issue of co-authoring with someone who had at the time just completed his 6th-form (according to the author bio.) was YOUR responsibility. Didn’t you point this out to your co-author’s parents at the time and get their approval for his participation in this publication? And indeed, if this wasn’t your co-author’s opinion, why is his name on the article? Thus, your attempt to criticise my citation of this work reveals evidence of your irresponsible behaviour. You have cited the same study on other occasions (e.g., your IATEFL talk a few years ago included a citation of it in the abstract, I recall). Thus, there is nothing false, fallacious or purile in my citing this article in which you note “Perhaps most persuasively, a recent meta-analysis by Bryfonski and McKay (2017) of TBLT implementation reports high levels of success and stakeholder satisfaction… Over 60 studies were analysed, and the results found a positive and strong effect for TBLT implementation across a wide variety of learning outcomes, and positive stakeholder perceptions towards a variety of TBLT programmes.” (Jordan & Gray, 2019, pp. 445-446).

And with regard to the persistence of the arguments, this is one thing that you have certainly shown for a long time. Mike Long has been arguing for stronger versions of TBLT since his focus on forms/form distinction which was over 30 years ago, so while I could tone down that point, you have both argued for its superiority persistently, even if you haven’t used that word. And with regard to the broader family and your rejection that anything else can work, have you forgotten about your many diatribes on, for example, PPP (I’m sure we can find some quotes if required), which my research has evidenced (Anderson, 2017), and other historians agree (e.g., Howatt, 1984) is certainly within the broader family of CLT approaches, albeit on the weaker end?

Perhaps you should acknowledge your error in repeatedly using this piece as evidence and for co-authoring a published article with a minor without their approval of the content?

LikeLike

LikeLike

You ask for evidence that you have argued that TBLT is superior. Here it is, from three sources of yours:

“Long’s TBLT is, in my opinion the best described and best justified syllabus currently available in ELT.” (see here: https://geof950777899.wordpress.com/2017/03/15/two-versions-of-task-based-language-teaching/)

“While I agree with all their criticisms of coursebook-driven ELT and I like their book, I’m more persuaded by Long’s appraoch, as laid out in Mike Long’s “SLA and TBLT”” (see here: https://geof950777899.wordpress.com/2017/07/21/against-walkley-and-dellars-lexical-approach/)

“We need to talk about coursebooks Geoff Jordan (University of Leicester)

Why do coursebooks still dominate ELT practice? Their methodology contradicts

SLA research findings, de-skills teachers, and leads to poor results (Long, 2015). This talk reviews the evidence against coursebooks, presents the case for task-based language teaching (Bryfonski and McKay, 2017), and argues that we need to talk more openly and critically about coursebooks and their alternatives.” (IATEFL Liverpool 2019 Conference Abstract of talk)

And with regard to the article of yours that I cite, I cite it as an example (note my use of “e.g.,” please) that proponents of stronger versions of TBLT, which I think it is reasonable to say you are (see above), have cited the Bryfonski and McKay article, which you also have. And I think it’s about right to say that these arguments of stronger proponents of TBLT go back about 30 years, even if you personally have been doing it only for 10 years or so! It is somewhat impractical for me to email every author of every article I cite as evidence to find out if the co-authors involved agree with a point made, regardless of whether the adults or children.

It’s nice to read more nuanced opinions from you as expressed in this final paragraph of your latest comment, but I think most people in the ELT community who know you are very much aware that you don’t always argue that “courses which use an analytical syllabus or in line with a solid research findings and thus more likely to be efficacious than general English coursebooks that implement a synthetic syllabus”, you openly lampoon such courses/teachers/curricula, as if anyone who adopts such a coursebook, writes one, or argues in favour of them is bonkers. You seem to remain blissfully unaware of how overworked and burnt out almost all teachers around the world are today, and of how your arguments that teachers should somehow develop their own materials for every course of learning not only puts pressure on teachers to work even harder, but also makes those who can’t do this (i.e., the vast majority) feel guilty. Where’s the social justice in this, when, as Bryfonski and McKay demonstrate, we can facilitate useful learning even in TSLT, which is amenable to synthetic curricula (and therefore adaptive, critical use of coursebooks), as I’ve always argued?

LikeLike

Hi Jason – I replied to this on LinkedIn but I felt that I should copy-paste it here for it to be more easily accessible.

Many thanks for bringing this up. Having reviewed the critiques, of course I accept that the Bryfonski & McKay meta-analysis was not good support for my assertion that TBLT is applied in many contexts around the world. This was my key aim in using it – I alluded to the positive effect sizes, but really I was trying to show that there must be many places where TBLT is transparent to the teachers using it. I can see that it doesn’t really show this and I will certainly treat this study with more caution in the future.

I hope it goes without saying that B&M (2019) is not evidence *against* my claim, but obviously I need to present positive support for my assertion. I could have done so with reference to numerous individual studies of TBLT programmes. I went for a convenient shortcut and I will need to do better.

I also hope you can acknowledge that the TBLT/TSLT distinction was not mentioned at all in my talk. I deliberately avoided unpacking strong/weak distinctions and I sidestepped other major issues of contention, such as “to NA or not to NA”. I clearly back programmatic TBLT, but as the audience included many early career teachers, I went for broader strokes. In a sense, however, advocating the “taskification” of the coursebook *was* a nod towards TSLT.

I do object to your implication that my talk promoted TBLT as a “sole best practice methodology”, as I explicitly referenced other communicative/analytic approaches and nowhere claimed that TBLT was superior to these. I also suggested on one slide that TBLT as a field needs to move beyond its dependence on support from SLA theory narrowly focused on the acquisition of forms (there is some evidence that it is already doing so), and I explored this further with Richard Smith in the Q&A. Finally, I resist the positing of the post-method condition as the answer to ELT’s ills, as much as Geoff Jordan might label me a postmodernist. I feel that coursebook-driven methodology requires a more consistent, coherent response – but I don’t say that this has to be TBLT.

LikeLike

Hi Neil, Thanks for this. Yes, I acknowledge these points to some extent. Note I stated “(sole) best practice” (I put sole in brackets because the notion of best practice implies better than the rest, and this is the danger in any best practice model – I think we need to talk about appropriate good practice). One of the issues with arguing for the superiority of implicit learning over explicit (which I recall you did argue), means that only an approach that adopts a reactive focus on form (which you also argued for), a-la Long’s perspective, is justified. This essentially devalues any approach that adopts a synthetic curriculum, something else, I recall, you argued against. My reason for writing this blog post, as I think I’ve made clear, is that the evidence (including Bryfonski & McKay, 2019) DOES support the use of tasks in synthetic curricula, which you also argue against. Once we recognise that they can work in synthetic curricula, we also open up the possibility that PPP can work, providing the final P is communicative, which I’ve frequently argued can be the case in my writing (e.g., Anderson, 2016, in the references) yet some, including Geoff Jordan, have denied is possible (see his comments on my blog post from 2016 here: https://jasonanderson.blog/2016/08/06/the-ppp-saga-ends/ and I’m sure elsewhere). The key point here, and one I’ve made repeatedly, is that we can move towards more communicative practices in mainstream educational contexts around the world if we stop assuming that these are not possible within synthetic curricula (which are endemic in such contexts), which I think you do imply, if not argue. We need to recognise a continuum here, from more to less communicative teaching, rather than an either/or approach – this opens up the space for gradual evolution, something I’m seeing happening, albeit slowly.

In this post, which isn’t just about your talk, I am reflecting more broadly on my concerns with what I sometimes call the SLA=TBLT argument that Long, Skehan, Ellis and Jordan all argue, often insistently, so that teachers feel that they are somehow wrong, or mistaken to use, or believe in the utility of, a synthetic curriculum and this devalues their work and impacts their self-confidence, which can be one of the impacts of presenting these arguments in an IATEFL plenary. I feel very strongly that we need to move on from this dangerously reductive perspective to understand and value all the important things that happen in language classrooms and why they all need to be part of the picture (see my 2024b reference in the blog post, open access), rather than reducing ELT to simply “instructed SLA” – it’s so much more than that.

LikeLike

Hi Jason. I was asked to do a talk on TBLT which, as far as I understand it, is an analytic syllabus type, based on learning-by-doing as opposed to learn-by-studying-then-doing. I therefore disagree that presenting it as such was dangerously reductive, and again I reject that I implied it was the “best practice methodology”, in which phrase “sole” seems to me redundant anyway. You seem to subscribe to the TBLT/TSLT distinction so I doubt you disagree that TBLT is on the analytic side, and TSLT on the synthetic. And although I was not asked to talk about TSLT, I was careful not to rule it out – perhaps not careful enough for you – but I deliberately avoided making the TBLT/TSLT distinction so I could keep things reasonably open while making my own preferences clear.

I did not argue against the use of tasks in synthetic curricula or imply that it was impossible to use them there. If indeed the inclusion of tasks improve synthetic curricula, then great -although this is no argument against TBLT. I simply said that such tasks are often difficult to spot, they may be surrounded by form-focused exercises which influence how they are interpreted by Ts and Ss, and I gave other obstacles in the way of teachers maximising their effectiveness in such contexts.

Yes, I do favour tasks being used in an analytic syllabus over a synthetic one, but I think it is a bit of a stretch to claim that this position ultimately devalues the work of teachers who follow synthetic syllabuses. My talk was primarily addressed at Ts who work in such circumstances. I believe the talk encouraged them to exploit tasks up to the point at which they have the inclination, freedom, training and resources to do so. I suggested they became less controllers and more facilitators in the classroom, that they gave more space to tasks than to exercises. And I gave suggestions as to how to incorporate explicit attention to form within a task sequence, as an alternative to pre-emptive focus on forms – because as you well know, as much as TBLT can be justified for trying to exploit implicit acqusition processes, the conclusion is not that explicit learning is dispensable.

I think many teachers in these contexts are open to doing more with tasks within their current syllabus, and I encourage(d) them to do so. However, alongside many other teachers I’ve worked with, I find it frustrating that the circumstances don’t often permit going further to embrace a more analytic approach, and I tried to say what would need to change for this to happen.

You can disagree that this is a good idea, you can argue for slow evolution over the more radical, probably mostly local disruptions I see as possible, but until we have more analytic TBLT programmes within the contexts we are discussing to compare with TSLT, or to give us a meta-analysis worthy of its claims, both of us are going to be on slightly shaky ground. However, until I see robust evidence to the contrary, I am more convinced that tasks should work better when students’ communicative needs take primacy over any external syllabus, and I think it’s enough that I kept my talk open to other possibilities. Tempering my argument further just because synthetic syllabuses are dominant in the ELT world is not a tenable position for me.

LikeLike

Hi Neil,

All noted, acknowledged and understood.

By the way, I’m not actually a fan of the TBLT-TSLT distinction, although I use the terms as shorthand for a difference that is recognised by others. I see a much more complex relationship between the implicit and explicit processes happening simultaneously for different learners in diverse ways in every classroom – a type of multiple complex dynamic systems theory, if you will. Understanding individual cognitive processes on their own can never explain these complexities. This is particularly true when we remember that the SLA=TBLT arguments are based almost solely on evidence about learning of structural elements (grammar) within language, rather than lexical ones. As Paul Nation and others have argued, the implicit learning of lexis is not constrained by the same complex acquisition sequences as grammar, and the explicit learning of both is also amenable to formal synthetic curricular, and of use in multiple ways to learners in both education and wider society, particularly important in all written language use – as such, the historical assumptions of so many psychocognitively focused SLA researchers concerning what type of learning is valid and what learners need are therefore erroneous today.

The reality is that most coursebooks today are actually thematically designed, with comparatively little explicit grammar focus at least compared to, say, 20 years ago, and as such, adopting a strong TBLT focus seems to run the risk of developing a more complex (analytical) curriculum to implement because of limited evidence regarding a fairly minor part of language learning (and this without even mentioning skills). I agree with you that we need more evidence if we are ever to work out whether the SLA=TBLT arguments are correct. But I just think there are much greater priorities within understanding and moving towards more effective teaching practices that are truly implementable in the majority of classrooms worldwide.

I see a continuum between lexis and grammar (hopefully uncontroversial), a continuum between implicit and explicit ways of knowing (see, e.g., Cleeremans and Jimeenez’s Dynamic Graded Continuum, 2002), and an even more complex relationship between the learning that is happening at any given point for any two learners in the same class. With all this in mind, I would still argue it is laughable (and I think you agree there were quite a few laughs and sighs when you suggested it) to suggest that those of us who teach in classes of over 30 learners for only a few hours a week (and this is the norm worldwide) can offer any meaningful explicit instruction to learners using a reactive focus on form approach. And this is why the Bryfonski & McKay study is important, because it demonstrates that such hard work simply isn’t necessary – let’s try to move in what we believe to be (and we might all be wrong here) a shared right direction, but starting from where the teachers are, rather than our own agendas – hence evolution, building on what teachers are already doing well, not abandoning this and implementing revolution based on insufficient evidence. For this learning to be useful and implementable, it must happen as closely as possible to the teacher’s own classroom (see, e.g., Guskey, 2002 – https://doi.org/10.1080/135406002100000512). I expand on some of these arguments in more detail in my response to Ellis in the point-counterpoint feature relating to my TATE model. See here, if interested:

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/340350819_A_Response_to_Ellis_The_Dangers_of_a_Narrowly_Focused_SLA_Canon

LikeLike

Thanks for this. I enjoyed the talk and this critique. I also wondered why Jane Willis has never been asked to give a plenary! At the same time, I wondered why there are never any plenaries about language itself.

I think perhaps the narrow debate on e.g. PPP vs TBLT bypasses many teachers given that CLT is yet to arrive in many contexts, something Van Patten once stated. *Teachers have other issues to consider such as large classes, poor resources, reliance on grammar translation etc etc. The bigger battle might be for adoption of communicative principles/approaches of ANY type in many contexts. It’s also why I think the idea of a ‘post method era’ is fanciful to be frank.

*An anecdote. At the last IATEFL I went to, I was in a talk where TBLT was being touted as superior to PPP. The assumotikn was that everyone agreed. A teacher next to me leant over and whispered ‘What is PPP’?

Thanks for the post.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Chris, Many thanks for this. I agree absolutely regarding PPP vs TBLT, and have found myself having to argue frequently to proponents of TBLT that a far more pressing issue than the debate of whether TBLT or PPP works better is the challenge of encouraging more teachers to move from doing just PP to adding on something more communicative at the end of the lesson. I’ve even watched my fair share of English language lessons that are just presentations without even any controlled practice. See my comments to Neil above in this regard, and my 2016 paper in the references.

Personally, I wouldn’t call aspirations towards post-method approaches fanciful, but would agree we need more complete, nuanced and realistic teacher education curricula to ensure that they can address the highly complex relationships between theory, practice and identity (see Korthagen’s work on Professional Development 3.0 – https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2016.1211523). It’s only when three of these intersect that we understand teachers, what they do, why they do it, and finally how they do it. And all of these are necessarily informed by an equally important question: How are they? And the current ’emotional turn’ in educational linguistics research is only beginning to address this vitally important element.

Nice anecdote. 🙂

LikeLike

I am familiar with some (though not all) of their work, but I’ve never seen any of them espouse such a view. Perhaps you could point towards some examples?

To offer some counter examples, in Chapter 13 of their book, Jordan and Long give examples of various alternative approaches to coursebook dominated ELT. Some of them include TBLT, and some of them don’t, such as dogme and use of storytelling in the Hands Up project. In his 2019 book, Ellis has also argued for a hybrid approach, combining elements of both TSLT and TBLT.

I don’t think anyone could possibly dispute the idea that “there is no best method”, but you can argue for this without consistently misrepresenting the views of others, as you have done above.

LikeLike

Hi Peter, Thanks for contributing. The ‘SLA=TBLT’ is a shorthand for the argument in the opinions of all of the authors I cite here that “SLA research findings” support TBLT more than many other approach (see Jordan’s IATEFL Liverpool abstract that I cite in response to his latest comment), problematically implying that the varied and nuanced findings of SLA research that are themselves, at times, even contradictory (see my above discussion of Bryfonski and McKay) all points solely to one conclusion (Brian Tomlinson also tries to imply the same). They do not, and this is therefore an oversimplification and misrepresentation of an increasingly diverse field of research. I acknowledge that some of them also offer arguments for other approaches, but I think it’s fair to say that all of these authors have, in their work, advocated more for TBLT than anything else. Certainly Mike Long’s 2014 book does this – the clue’s in the title: “Second Language Acquisition and Task-Based Language Teaching”.

LikeLike

OK, thanks for the clarification. I think all of these authors would probably agree that the findings from SLA research show that grammatical forms are learnt irrespective of the order they are taught. This is a view shared, I believe, by most of the SLA research community. As such, a synthetic approach to syllabus design does not respect each learner’s individual syllabus. For me, TBLT is a reaction to this as one of a number of possible approaches. I don’t see any of these authors arguing that TBLT is a panacea to the problems on ELT, nor should their support for TBLT override any constraints placed on teacher’s by their local context.

Where I think we can both agree (and I think the aforementioned authors would too) is that imposing TBLT on teachers is not the way to go, and that numerous research studies from various contexts have borne this out.

Whilst not directly stated, I think the same idea was implicit in Neil’s talk, and I feel he gave a good introduction of how interested teachers might be able to start to incorporate tasks into their lessons, should they wish to do so.

LikeLike

Hi Peter,

Many thanks again. This depends on how you define and value learning. And here I think we need to make a distinction between different parts of the language teaching and learning community and recognise huge biases in the origins of applied linguistics in the western Anglosphere in the 1960s-70s, and the need for us to recognise a much wider range of perspectives when defining such a key term (think, for example, how explicit knowledge about language plays an integral role in our writing skills and how such skills are vital for the vast majority of learners in the world today learning English primarily if not solely for educational purposes – explicit knowledge learning does not follow the same rules as implicit knowledge – see my comments on this to Neil). Within the psychocognitively focused SLA community, there has been a grave misunderstanding, originating essential in Chomskian linguistics, that the only type of valid learning is implicit “acquisition”. This is very far from the truth for the vast majority of language learners in primary and secondary classrooms today (see Anderson, 2024b, in references above). It’s also very clear that within that community there has been strong opposition towards alternative perspectives and ways of looking at and conceiving of language and learning, two terms that incorporate a lot, with, for example, a Hallidayan perspective offering a very different understanding of the relationship between these (and I haven’t here even touched upon different understandings within wider educational discourse or Southern theory). Indeed, this discussion led to the sociocultural turn in applied linguistics, at a time when disputes and disagreements were very heated. Jim Lantolf (de Bot, 2015, p. 61) recalls “I still have scars from that” – it was certainly not an inclusive community or conversation. Mike Long was one of the primary protagonists objecting to the sociocultural turn, arguing for a reductive, rationalist approach to language learning research (sometimes co-authoring with Geoff Jordan on this; Gregg et al., 1997), rather than the ‘Letting all flowers bloom’ perspective of Lantolf; 1993) and attempting to engage in what he called “theory culling” (Long, 1993, in references), and the promotion of his highly problematic perspective that I typify as SLA=TBLT. What was at stake here was understanding what it is we are trying to understand as educational linguists/applied linguists. Since the sociocultural turn, there has been increasing discussion of how this field is conceived and what we need to focus on. Many of us today even have concerns about the term “second language acquisition”, and choose alternatives (see Anderson, 2022; Larsen-Freeman, 2014; Leung & Valdez, 2019), because of the problematic simplistic and reductive nature of this phrasing. As somebody who learnt to teach and to train teachers at this time (working mainly in the Global South) I was constantly being fed a distorted discourse that seem to completely overlook, and therefore disadvantage, the reality, norms and cultural factors influencing who we are as language teachers what we do and why – only then can we move onto the how question that methodology addresses. Psychocognitively focused research is fine, but always limited, and we need much more ecologically valid research, not just about what promotes learning, but to understand what is happening in classrooms, how and why and where we might go to ensure that we improve the educational experience without devaluing or overlooking important elements of it (Anderson, 2023).

References

Anderson, J. (2022). What’s in a name? Why ‘SLA’ is no longer fit for purpose and the emerging, more equitable alternatives. Language Teaching, 55, 427-433 . https://doi.org/10.1017/S0261444822000192

Anderson, J. (2023). Teacher expertise in the global South: Theory, research and evidence. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009284837

LikeLike

Hi again Jason – as I can’t seem to reply to your previous comment (beginning “all noted”), I’ll start a new one.

I am aware of your position and thanks for outlining it further.

I just take issue with the “laughable” comment re. reactive focus on form. Pure, immediate reactive FonF in the form of recasts was given as *one* option among many for pushing sts to notice and/or take risks with language within a TBLT framework, and it came with appropriate caveats. I think here that you are the one being dangerously reductive about the options available to focus on form within a broad focus on meaning. Skehan, who you lumped in with Long in an earlier comment, disagreed strongly with Mike about the potential of recasts/meaning clarifications, and I have some sympathy for his views. Correspondingly, much of what I suggested in the latter part of the talk came from Skehan’s processing perspective.

LikeLike

Noted, but it still was suggested, and you were yourself aware that this was a big ask! I take your point that I’m being reductive. I could have mentioned the really interesting approach being investigated by colleagues at International House London, regarding how they work with emergent language. While I still think this would be immensely challenging in normal-size mainstream classes, it certainly works well for them. I suspect you are familiar with Richard and Danny’s book: https://pavpub.com/pavilion-elt/working-with-emergent-language?srsltid=AfmBOop8_UtTRdayxONtBlzsQRBqDA89I-ya4yU5vPj8Ipj47giio7h4

LikeLike

Thanks for the long reply above, Jason. Yes, I use ‘learning’ to mean the development of implicit language knowledge, and I use it for the same reason as Neil referred to in his talk, because ‘it is automatic and fast … and is assumed to be more lasting’ (than explicit knowledge).

From my perspective as someone who spends a lot of time teaching writing, I see on an almost daily basis how fairly advanced learners fail to incorporate even the supposedly most simple so-called ‘rules’ into their writing, so I’d question whether explicit knowledge really does play an integral role in writing skills. And this all without questioning the psychological validity of the kind of rules that learners typically encounter in textbooks and grammar reference materials.

When it comes to sociolinguistics, it’s always useful to look at things through a different lens, but I often feel that ideas emanating from this field are often more theoretical than practical in nature. If it could offer more tangible advice to teachers, then I’d be more much willing to explore it in depth. For example, there seems to be a lot about translanguaging around at the moment, but the implications for teachers don’t seem to amount to much more than ‘don’t force your students to use the L2 all the time in class’, which is probably what most teachers already do anyway.

LikeLike

Thanks again Peter. The reasons why your learners make mistakes are, of course, complex and varied and probably also extend to implicit knowledge (I know I make plenty in my English use). I’m not sure why you mention sociolinguistics – this is of course part of the background theory to the issues involved, but the social turn is about understanding the role of the social and the cultural in (language) learning and encouraged a shift (that was already underway) away from the assumptions predominant in the psychocognitive SLA community that we can understand learning using theoretical frameworks that focused predominantly on individual or transactional (rather than interactional) information exchange processes. And regarding translanguaging, see, for example the CUNY NSIEB translanguaging guides and Garcia et al (2017) – plenty of guidance there, or Cenoz and Gorter’s 2020 book. With some expertise in this area myself (e.g., Anderson, 2024), I can confirm this is much more than ‘‘don’t force your students to use the L2 all the time in class’. One question for you to reflect upon: Has your education ever been hindered by a policy (official or covert) that denies you the right to use the languages that you know best to learn? Millions, probably billions of learners have. But if you have no lived experience of this, you may not understand why translanguaging is so important – and as I argue in the above, English is part of the colonial legacy doing this, and is spilling out of the subject classroom in complex and diverse ways.

LikeLike

Thanks for the links to information about translanguaging. Of course, you are right that the implications for translanguaging on teachers are certainly more than what I stated above, and I was too flippant in that regard. When I was thinking about its usefulness to teachers though, I didn’t have the kind of teachers that the CUNY-NYSIEB guides were written for and I am sure that the suggested activities are indeed useful in contexts such as the US education system where minority languages may often be wrongly stigmatized.

Reading your ELTJ article about translanguaging, I have to say that I didn’t see that much practical advice for English language teachers beyond what I would just see as common sense. For example, the use of bilingual dictionaries or first language glosses are of course to be encouraged, but I can look to research into vocabulary acquisition to support that rather than relying on some abstract theory of language.

You rightly refer to damaging language policies, but sadly this, and many of the other valid issues you raise in your article such as the nature of exams, writing conventions, etc. are beyond the scope of teachers to do much about.

LikeLike

Thanks for acknowledging this. One of the advantages of publishing in ELT Journal is that it may also have an impact on policy and curricula (fingers crossed!); the article wasn’t really intended as a practical guide, although it does include broader implications for practice. With regard to such a guide, for English language teachers this is always so challenging because contexts vary so much. So guidelines always need to be context specific (back to the issue of post-method principles rather than methodology; see Kumaravadivelu on this), but a colleague and I are in the middle of writing a practical book, specifically for English language teachers on translanguaging. We hope it will be available next year.

LikeLiked by 1 person

For someone who just started experimenting with TBLT/TSLT and the nuances of it because of Module 3, all of this is eye-opening. Thanks for sharing!

LikeLiked by 1 person

radiant! 52 2025 Methodological monocultures or ecosystems? A few reflections and cautions on an IATEFL plenary grand

LikeLike