In our recent paper (Mahapatra & Anderson, 2022), Santosh Mahapatra and I propose a multilingual curricular framework for Indian educational boards, which we call ‘Languages for Learning’ (LFL). We argue that LFL can provide a suitable basis for multilingual education across primary and secondary curricula, addressing learning in both content subjects and language subjects, appropriate to India’s recently revised National Education Policy (Government of India, 2020), which supports and encourages multilingual practices in the classroom.

In this co-authored blog post, we provide a brief overview of LFL for those who do not have academic access to the paper, and also explore how it may also be appropriate to other multilingual contexts across the Global South.

Why ‘languages for learning’?

We propose the term ‘Languages for Learning’ (LFL) as a more appropriate alternative to ‘Medium of Instruction’ (MOI) for developing language-in-education policy in multilingual contexts. We view ‘languages for learning’ as better able to describe the complex learning affordances of multilingual classrooms because it combines an emphasis on multilingual inclusivity (‘languages’ rather than ‘medium’) with a focus on ‘learning’ (as in learning-centred education) rather than ‘instruction’. Perhaps most importantly, the ‘for’ in LFL enables us to frame languages as facilitative (resources), rather than restrictive (impedances), of learning.

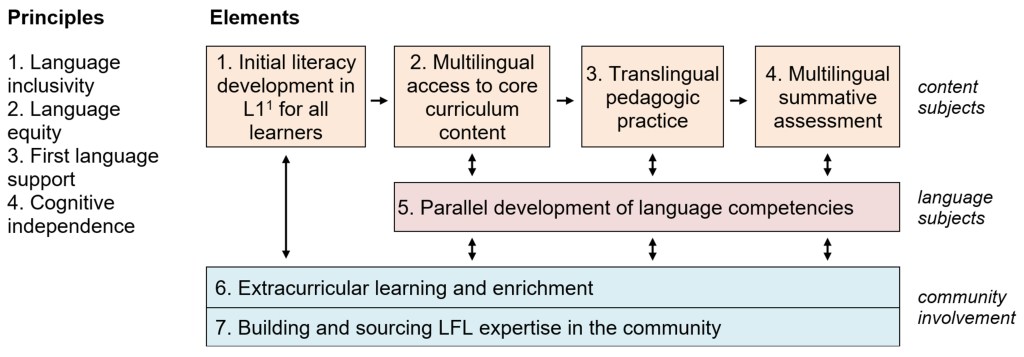

In the paper we present the following framework as one of many ways for how a LFL approach could be integrated into education in mainstream curricular contexts.

The languages for learning framework

Note. ‘L1’ in the framework refers to the closest variety possible to the learner’s primary home language.

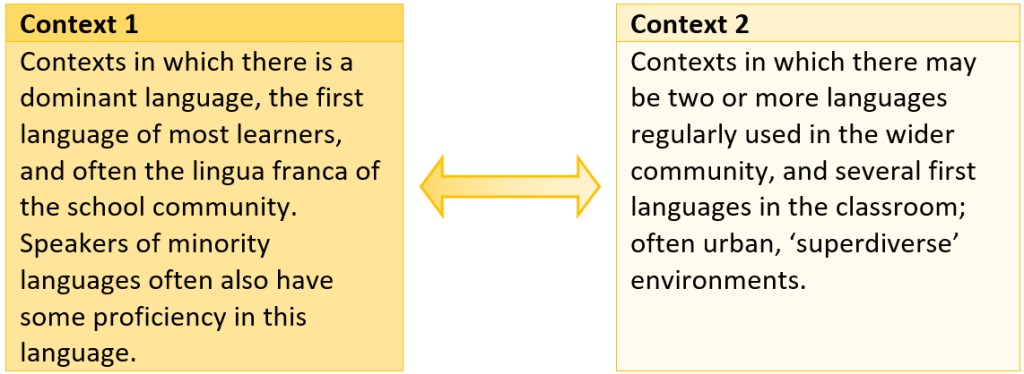

The LFL framework includes four principles and seven potential elements (see Figure 1) that would need to be operationalised differently in each context, depending on the languages involved and the needs of learners and other stakeholders. It is adaptable to two common language community contexts found in basic education (primary and secondary) around the multilingual world (e.g., Cameroon, Kenya, Indonesia, Papua New Guinea, Uganda), as well as contexts part-way between these:

Note. See here for ‘superdiverse’.

In the framework, ‘content subjects’ refers to subjects such as maths, sciences and humanities in national curricula. ‘Language subjects’ includes what is often called ‘first’ language (not always the home language of all learners) and ‘language arts’, as well as second and other additional languages. In some contexts, such as India, this often involves not only several languages, but also multiple written literacies (i.e., scripts) and languacultural traditions.

The four principles of the LFL framework

The LFL framework is underpinned by four pedagogic principles that can be promoted across the education system, as follows:

(1) Language inclusivity: All languages are welcomed and equal in the classroom. While learners may be required to adopt specific languaging practices for assessment and outcomes-oriented purposes (as defined by curricula), a teacher would always seek to prioritise learner participation in classroom discourse over language choice.

(2) Language equity: Creating a classroom community that neither excludes nor prioritises certain languages reduces the threat that dominant languages may pose to learners’ (and their families’) identity, self-esteem and rights. The removal of such threat may increase learner motivation to study and learn these languages.

(3) First language support: Whenever required, learners have access to mediation (through peer, teacher and parental/caregiver support) and resources (e.g., expository texts, bilingual dictionaries/electronic translation, multilingual wall charts, etc.) to facilitate access to curriculum content and skills development, both in class and between lessons.

(4) Cognitive independence (in content subjects): To ensure that those learners who are less enabled in a dominant classroom language have equal (or as equal as practically possible) access to learning, it is recognised that cognitive development is separable from language proficiency. Whenever possible, learners are offered opportunities to demonstrate their understanding of curriculum content in preferred languages, including during both formative and summative assessment.

(Mahapatra & Anderson, 2022, p. 9)

These four principles serve as an ideological foundation for the seven elements that follow, and may be promoted in both LFL classrooms and teacher education programs.

The seven elements of the LFL framework

The first of the seven elements concerns early (pre- and lower primary) grades; the remainder focus on higher primary and secondary grades (typically 4-12), when learners from different first language backgrounds are more likely to be studying together:

1) Initial literacy development

Consistent with current recommendations for mother-tongue-based multilingual education (MTB MLE) around the world (e.g., Benson, 2019; Heugh et al., 2019; Simpson, 2019; UNESCO, 2018), the LFL framework stresses the need for learners to begin orthographic literacy development (i.e., reading and writing) in their first (or closest possible) language in early grades, ideally with teachers who share such languages/dialects. Where required, minority language support organisations would be invited to help develop any resources required (discussed below).

2) Multilingual access to core curriculum content

Most schools/programs today offer core curriculum content (e.g., textbooks, supplementary TLMs) for each subject in one language only – the so-called ‘medium of instruction’. In the LFL framework this core curriculum content is available in all classroom languages (i.e., the L1s of all the students and the teacher); while this may be challenging in some contexts, print-on-demand technology and auto-translation software make this ever more possible today than previously. If this is not possible (e.g., unwritten languages), each learner would be able to choose from the available languages, rather than the authorities selecting this.

3) Translingual pedagogic practice

At the core of LFL are the spoken languaging practices of the classroom. Unlike scaffolded MOI approaches (e.g., CLIL1), in which other languages typically play a temporary role, in the LFL framework all classroom languages work together to support learning across the curriculum as required. This results in the fluid integration of resources from multiple languages typically referred to today as translanguaging (see Conteh, 2018; Wei, 2018).

“Languages enable learning, learning enables languages, and both of these are enabled by the community and its interactions.”

Mahapatra & Anderson, 2022, p. 11

While exact practices may vary depending on context, level and curricular goals, the following illustrative examples are provided in the paper, consistent with the four principles of LFL:

- The teacher may present new content monolingually (e.g., in Context 1) or multilingually (e.g., in Context 2), while some learners (e.g., speakers of minority languages) simultaneously gloss supplementary resources printed in an additional language, if required.

- Learners may work collaboratively in both shared-L1 and mixed-L1 groups, depending on task complexity, class composition, and stage in a unit of study.

- Learners may work individually using core curriculum content presented in their chosen languages (e.g., expository texts, exercises).

- Learners may give presentations in languages of their choice, including translingually (combining resources from several languages). Members of the classroom community (including the teacher) who do not share the presentation languages may seek mediation support from others who do.

- Learners may engage in activities targeting the development of ‘translingual competence’ (see Anderson, 2018), as used in the original translanguaging approach developed in Welsh bilingual secondary classrooms (Williams, 1996); for example, a project encouraging learners to access content in one language (e.g., a text in English), and respond to it in a different one (e.g., presentations on the text in Marathi).

- Project work is offered throughout the curriculum, and includes developing multilingual resources (e.g., posters or graphic organisers) to further strengthen multilingual learning and awareness.

(Mahapatra & Anderson, 2022, p. 11, summarised)

The practices described here are based, in large part, on observations made recently in the classrooms of expert Indian teachers (see Anderson, 2021, 2022). They would lead to a gradual, organic expansion of the community’s languaging resources, with speakers of minority languages being exposed to, and learning, majority languages, and vice versa; practices that largely mirror those in multilingual societies. Importantly, they would facilitate, what we might see as a blooming of all flowers, rather than transition from one monoculture to another, as typically happens in MOI approaches (i.e., “subtractive bilingualism” in practice; see, e.g., Cummins, 1986).

4) Multilingual summative assessment

In the LFL framework curriculum authorities would allow for summative assessment of content subjects in all learners’ L1s, consistent with Benson’s (2019) proposals for MTB MLE; the principle of cognitive independence empowers stakeholders to make informed decisions in this area. Learners and their parents/caregivers, supported by teachers, can choose the languages of assessment for each content subject separately each year, allowing changes to occur when learners are ready. In differentiating this choice, the LFL framework recognises the reality of individual differences in subject-specific competencies among learners, and reduces the negative impact of sudden transitions to English (see Simpson, 2019; UNESCO, 2018), which often happens in several subjects simultaneously in MOI and CLIL education. Further, in LFL, these transitions can be managed by teachers in the same institution, rather than between primary and secondary school, as often happens. Multilingual exam materials may also be possible (e.g., using parallel text); see Mbude-Shale et al. (2004) for a similar innovation.

5) Parallel development of language competencies

In language subjects, only the first three LFL principles would apply (excluding cognitive independence); pedagogic practices for both literacy and oracy of the language subject, would be adapted to learner proficiency and stage. For example, in early secondary grades, a teacher may encourage translanguaging among learners when discussing texts written in an exogenous language (e.g., English), or suggest learners make integrated use of L1 resources during writing tasks if required (see Figure 3). As proficiency develops, learners would be encouraged to produce texts, conduct discussions and give presentations in the subject language only (i.e., ‘monolanguaging’; Anderson, 2018), facilitating gradual, scaffolded progression towards additional language proficiency, something that is recognised within the framework as important, both to learners’ future studies and employment (see Joseph & Ramani, 2012).

Note. Personal details are anonymised.

6) Extra-curricular learning and enrichment

Because the LFL framework is inclusive of learners’ first languages, it is also inclusive of communities where their languages are used. This has two important implications for extra-curricular learning of the whole community (not just school-goers) and reciprocal enrichment:

- Firstly, it empowers parents/caregivers who have low levels of proficiency in what are typically dominant languages of education (e.g., English, Hindi). LFL enables them to monitor and support their children’s learning and play a more active role in their education than would otherwise be possible. If they have orthographic literacy, they can support their children’s development closely. If not, they can still follow it (e.g., children can read texts aloud to parents). Further community support may be available through locally-developed initiatives (e.g., homework study groups).

- Secondly, expertise in the local community can play a more active role in learning, both in the school (e.g., visits from community leaders to present on local initiatives in social studies lessons) and outside it (e.g., forest walks led by folk-botanists in science lessons), thereby supporting the preservation of valued traditions and community knowledge. This may also increase ownership of parent-teacher associations and school management committees, something that is frequently a challenge in contexts where there is a language disjoint between schooling and community.

7) Building and valuing multilingual expertise in the community

We recognise that the proposed LFL framework would require significant investment, both financial and temporal to build the necessary skills. It would require a range of community resources in order to work effectively, including translation services (e.g., of texts, exam papers), multilingual expertise among staff (e.g., writing exam papers) and the development of supplementary resources (e.g., bilingual dictionaries, early childhood primers, etc.).

“Society can benefit from language diversity.”

Hogan-Brun, 2017, p. xiii

However, consistent with Hogan-Brun’s (2017) concept of linguanomics, we view LFL as capable of having a positive economic impact, particularly in what are often disadvantaged communities due to the minority status of their languages. The investment required by LFL would provide useful work opportunities for speakers of minority languages, supporting and valuing the preservation of their languages, cultures, knowledge and skills, something that is widely recognised as important to the wider cultural heritage of many countries, including India (Government of India, 2020). In this sense, the LFL framework would support the development of language-specific expertise that would have further knock-on impacts (e.g., the establishment of new roles and institutions, the funding of minority language literature, etc.). This may contribute to reducing the marginalisation of minority language users, and create a new economy based on language diversity.

The challenges ahead

In the paper, we reflect critically on the challenges that such an ambitious framework would present, particularly in education systems with low levels of investment, as frequently found across the Global South. These challenges include:

- the need for carefully monitored piloting of such an approach before wider implementation

- the potential naivety of attempting to separate language from content that is implicit in the notion of cognitive independence; content and language are closely interconnected in cognitive schemata

- despite our ‘pitch’ for an economy based on multilingualism, the required capital investment is likely to be significant, both initially and ongoing

- some parents/caregivers may object to the LFL framework, believing that early monolingual immersion in dominant languages through schooling will lead to educational success for their children, despite the extensive evidence that, particularly in low-income contexts, this is more likely to lead to failure (Simpson, 2019; UNESCO, 2018); in contexts where such beliefs are prevalent, evidence from pilot projects and extensive community engagement will be necessary to the success of LFL

Nonetheless, our combined experience of education in a wide range of multilingual contexts tells us that many of the practices recommended above already happen unofficially (see discussion of the “hidden pedagogy” of text interpretation here). What we are arguing for is that these practices not only become legitimised, but theorised and formalised, so that they can be structured, supported and monitored appropriately. As such, we offer LFL as a contribution to ongoing discourse on how multilingual education can move away from the “monolingual habitus” (Liddicoat, 2016) that has limited education in multilingual communities for so long.

Notes

1. CLIL: Content and Language Integrated Learning. See here.

References

Anderson, J. (2018). Reimagining English language learners from a translingual perspective. ELT Journal, 72(1), 26-37. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/ccx029 (click thru here)

Anderson, J. (2021). Eight expert Indian teachers of English: A participatory comparative case study of teacher expertise in the Global South. [Doctoral dissertation, University of Warwick]. Warwick WRAP. http://wrap.warwick.ac.uk/159940 [Open Access]

Anderson, J. (2022). The translanguaging practices of expert Indian teachers of English and their students. Manuscript submitted for publication.

Benson, C. (2019). L1-based multilingual education in the Asia and Pacific region and beyond: Where are we, and where do we need to go?. In A. Kirkpatrick & A. J. Liddicoat (Eds.), The Routledge international handbook of language education policy in Asia (pp. 29-41). Routledge.

Conteh, J. (2018). Translanguaging: Key concepts in ELT. ELT Journal, 72(4), 445-447. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/ccy034 [Open Access]

Cummins, J. (1986). Empowering minority students: A framework for intervention. Harvard Educational Review, 56(1), 18-36. [Available here]

Government of India (2020). National education policy 2020. [Available here]

Heugh, K., French, M., Armitage, J., Taylor-Leech, K., Bilinghurst, N., & Ollerhead, S. (2019). Using multilingual approaches: Moving from theory to practice. A resource book of strategies, activities and projects for the classroom. British Council. [Available here]

Hogan-Brun, G. (2017). Linguanomics: What is the market potential of multilingualism? Bloomsbury Publishing.

Joseph, M., & Ramani, E. (2012). “Glocalization”: Going beyond the dichotomy of global versus local through additive multilingualism. International Multilingual Research Journal, 6(1), 22-34. https://doi.org/10.1080/19313152.2012.639246

Liddicoat, A. J. (2016). Multilingualism research in Anglophone contexts as a discursive construction of multilingual practice. Journal of Multicultural Discourses, 11(1), 9-24. https://doi.org/10.1080/17447143.2015.1086361

Mahapatra, S. K., & Anderson, J. (2022). Languages for learning: a framework for implementing India’s multilingual language-in-education policy. Current Issues in Language Planning. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/14664208.2022.2037292

Mbude-Shale, N., Wababa, Z., & Plüddemann, P. (2004). Developmental research: A dual-medium schools pilot project, Cape Town, 1999–2002. In B. Brock-Utne, Z. Desai & M. Qorro (Eds.), Researching the language of instruction in Tanzania and South Africa (pp. 151–168). African Minds.

Simpson, J. (2019). English language and medium of instruction in basic education in low- and middle-income countries: A British Council perspective. London: British Council. [Available here]

UNESCO (2018). MTB-MLE resource kit: Including the excluded: Promoting multilingual education. UNESCO Bangkok Office. [Available here]

Williams, C. (1996). Secondary education: Teaching in the bilingual situation. In C. Williams, G. Lewis, and C. Baker (Eds.), The language policy: Taking stock. CAI.

Wei, L. (2018). Translanguaging as a practical theory of language. Applied Linguistics, 39(1), 9-30. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/amx039

Thank you so much for your valuable resource.

On Thu, 17 Feb, 2022, 7:55 pm Jason Anderson: Teacher educator & author, wrote:

> Jason Anderson posted: ” In our recent paper (Mahapatra & Anderson, 2022), > Santosh Mahapatra and I propose a multilingual curricular framework for > Indian educational boards, which we call ‘Languages for Learning’ (LFL). We > argue that LFL can provide a suitable basis for mult” >

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks a lot for such a worth sharing!

Will read thoroughly.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you Jason Sir 🙏

On Thu, Feb 17, 2022, 7:55 PM Jason Anderson: Teacher educator & author wrote:

> Jason Anderson posted: ” In our recent paper (Mahapatra & Anderson, 2022), > Santosh Mahapatra and I propose a multilingual curricular framework for > Indian educational boards, which we call ‘Languages for Learning’ (LFL). We > argue that LFL can provide a suitable basis for mult” >

LikeLiked by 1 person