My latest research paper, co-authored with Amy Lightfoot of British Council S. Asia, explores the complexity of language use practices in English language classrooms across India. It reports on a survey (quantitative and qualitative) that we conducted with 169 Indian teachers last year, and sought to find out about what have traditionally been called ‘L1-use practices’ from a more inclusive, holistic perspective.

Given the richness and complexity of India’s linguistic diversity, we were interested to find out not only how Indian teachers and learners involve other languages in the English classroom, but also to what extent the translingual practices (where languages blend, switch, separate or even subvert, depending on situation and interlocutor; Canagarajah, 2013) documented extensively in Indian society extend into the classroom, both as a reflection of, and as preparation for, participation in this society, in line with the practices of a “translingual teacher” (Anderson, 2018, p. 34).

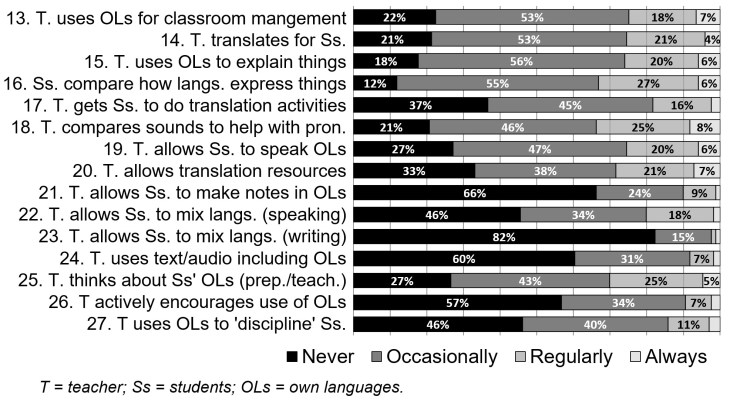

To this end, we asked a number of questions not previously asked on ‘L1-use’ questionnaires, including whether learners were encouraged to use other languages (OLs), whether contrastive analysis both of grammar and pronunciation took place (“crosslanguaging”, Anderson, 2017), and whether learners mixed languages in spoken or written form during lessons (“meshing”, Canagarajah, 2013).

Findings

Self-reported data should always be treated with caution. Especially where teachers feel pressure to avoid using OLs (quite frequent in our data) they are likely to under-report such use. Nonetheless, almost all respondents reported using OLs at times, although most reported doing so only occasionally. Comparing and contrasting languages (rarely asked about on previous ‘L1-use’ surveys) were among the most common practices reported, but only a small number of respondents reported actively encouraging use of OLs, and most did not consider it appropriate to do so during skills practice, especially in student written work (see Figure 1).

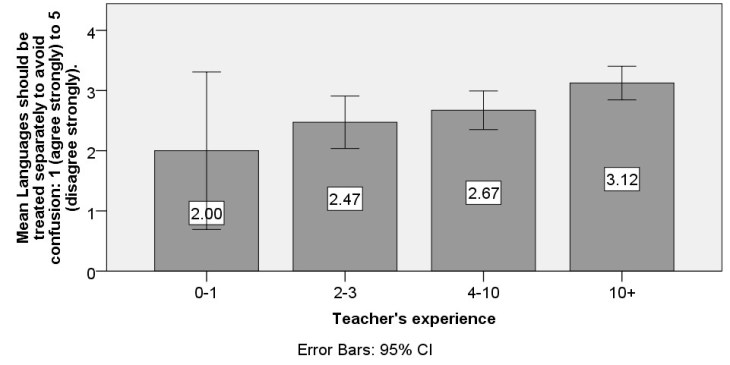

We found statistically significant associations (not necessarily causation) between how frequent such practices were and three other variables; school type (private school teachers reported less use), school MOI (unsurprisingly, teachers in English-medium schools reported less use, although not much less!) and, interestingly, teacher experience “with more experienced teachers reporting freedom to use OLs [other languages] and willingness to mix languages in class” (p. 14, see Figure 2). It was notable that several of the respondents who reported more OL-inclusive practices were teacher educators, including the following, a well-known teacher educator from a nodal institution in India:

In order to develop their listening skills, I’ve exposed them to Hindi songs before sharing English songs. For our Cultural evenings, we encourage them to present some typical song or dance from their country (for foreigners) or state (for Indians). (p. 14)

Figure 2: Teachers’ beliefs on treating languages separately by experience (figure 10 in paper).

A rural-urban continuum

Our data provides clear evidence of something all teachers and teacher educators in India are aware of, what we have called a “rural-urban continuum” (also see Hnatkovska & Lahiri, 2012), with linguistic diversity increasing as contexts become more urban, reducing the likelihood of teachers and learners sharing other languaging resources. Regression analysis that I conducted (but was not reported on in the paper due to concerns with confidence intervals) suggests that this is probably the strongest influence on teacher likelihood of OL use (see Table 1). We note that urban teachers very likely need to adopt different approaches to OL use to rural teachers, and provide examples of innovative practices, such as peer support to scaffold learning in super-diverse urban environments.

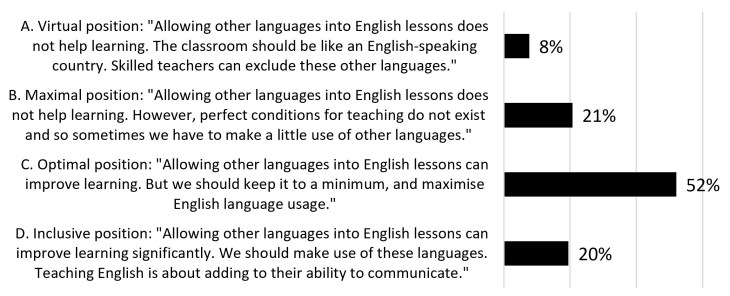

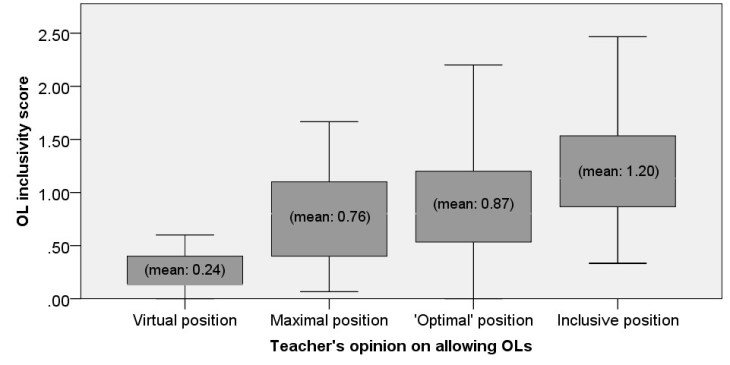

Macaro’s codeswitching positions extended

The paper also builds critically on Macaro’s framework for codeswitching (2001), proposing, and providing empirical support for an additional ‘inclusive position’ (see Figures 3-4) that goes beyond his ‘optimal position’. We suggest that

…his so-called ‘optimal position’ might more accurately be labelled a ‘judicious position’ given that the normative question of which position is ‘optimal’ requires further research and is likely to vary depending on context. (p. 16)

Recommendations

We provide recommendations broadly in line with national (e.g., NCERT) policy documents, particularly recommending more exploration of multilingual practices in teacher education (as does Durairajan, 2017) to reduce the likelihood of “guilty translingualism” in the classroom and encourage more principled practices founded on greater understanding of how languaging systems develop in multilingual contexts, and also recommend more grass-roots level research conducted in Indian classrooms to inform India teaching practices. We conclude by recognising the immense complexity of the many cultural, social and political systems that make up education in India, and echo Mohanty’s (2009, p.121) concern that the “exclusion and non-accommodation of languages in education denies equality of opportunity to learn”, often impacting most strongly on the most disadvantaged children.

The paper has been made open-access (courtesy of British Council India), so anybody can read it here or download the pdf here.

DOI ref: https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050.2018.1548558

Watch my ELTAI 2017 symposium plenary on translingual practices in India here, courtesy of British Council India:

References

Anderson, J. (2017) Translanguaging in English Language Classrooms in India: When, why and how?” Paper presented at 12th International ELTAI Conference. Ernakulum, India, June 29-July 1 (see “crosslanguaging” at 30:30 minutes): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=w93mMJzGgnA

Anderson, J. (2018). Reimagining English language learners from a translingual perspective. ELT Journal, 72,1, 26-37. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/ccx029 [ click here to avoid paywall ]

Canagarajah, S. (2013). Translingual practice: Global Englishes and cosmopolitan relations. Oxon, UK: Routledge. [ click here to open in Google books ]

Durairajan, G. (2017). Using the first language as a resource in English language classrooms: What research from India tells us. In H. Coleman (Ed.) Multilingualisms and Development: Selected Proceedings of the 11th Language and Development Conference, New Delhi, India (pp. 307-316). London: British Council. [ click here to open pdf ]

Hnatkovska, V. & Lahiri, A. (2012) The rural-urban divide in India. International Growth Centre Working Paper. London, IGC. [ pdf available here ]

Mohanty, A. K. (2009). Perpetuating inequality: Language disadvantage and capability deprivation of tribal mother tongue speakers in India. In W. Harbert, S. McConnell, A. Miller, & J. Whitman (Eds.) Language and Poverty (pp. 102-124). Toronto: University of Toronto Press. [ click here to open in Google Books ]