Rod Ellis recently proposed (2019) a modular framework for curriculum design in language teaching combining task-based language teaching (TBLT) and task-supported language teaching (TSLT). When I first read his proposal, I was somewhat surprised, because these two approaches are often perceived as incompatible (e.g., Long, 2015), based as they are on very different theories of learning. I found Ellis’s framework interesting, and also an apparent shift from his earlier position (e.g., 2003), when he tended to advocate task-based language teaching (TBLT) only, and critiqued task-supported language teaching (e.g., Harmer’s ESA, 1998) as irreconcilable with the cognitive SLA research evidence generally supporting a natural order theory of ‘acquisition’ (at least with regards to grammar) that is not amenable to the selection, ordering and teaching of specific structures within what we might call a ‘synthetic syllabus’.

Concerns with Ellis’s framework

Yet, as I read Ellis’s proposal, I also felt that it harboured a number of weaknesses, particularly its lack of attention to lexis, which most definitely is amenable to a synthetic syllabus (see Elgort & Nation, 2010), and is at least as important as grammar in language learning. As Krashen once said “when students travel, they don’t carry grammar books, they carry dictionaries” (cited in Lewis, 1993). But also the belief, often widespread in the cognitive SLA literature, that if we provide prior ‘instruction’ (i.e., an explicit language focus, as in a grammar clarification stage) of any sort, tasks can no longer facilitate useful learning. My view is that even if we do provide such instruction on one aspect of the language, as long as the activities we do are meaningful, they will provide opportunities to draw upon a much wider range of language (grammar, lexis, phonology, functions, etc.) than the area of instruction. For example, a story-writing task may be included to practise the use of narrative tenses, but would also require the use of articles, sequencing adverbials, prepositional phrases, adverbs of manner, finite and infinite verb clauses, and much more, all of which would be learnt more implicitly through both receptive and productive skills activities in such a lesson.

Ellis’s paper inspired me to respond (Anderson, 2020a), first with a critique of his framework, and then a counterproposal, one that builds upon the CAP(E) framework that I have argued (e.g., Anderson, 2017a, and here) is essentially endemic to current global coursebook design (much more than PPP). I wondered whether this model could be tweaked, both to embed integrated skills practice, and to include Nation’s (1996) ‘four strands’ of effective lexical learning (meaning-focused input, meaning-focused output, language-focused learning, and fluency development). I also considered how it might allow for an emergent language focus (e.g., Andon and Norrington-Davies, 2019; see here), so that opportunities for both pre- and during or post-task form foci could co-exist, as they do in the lessons of many experienced language teachers I have worked with. I was also interested in developing a framework that could encompass multilingual practices—particularly translanguaging—and also extend to a wide range of lesson types and approaches, including project-based learning, CLIL and text-based language teaching. I came up with, what I have called the ‘TATE model’ (Text, Analysis, Task, Exploration), and sent it to ELT Journal, where it was accepted, here.

The editor of the journal, Alessia Cogo, rightly thought it appropriate to give Rod Ellis an opportunity to respond to my critique, proposing a Point-Counterpoint feature. Rod was kind enough to do so, see here (Ellis, 2020), to which I was given the opportunity to reply, see here (Anderson, 2020b). All are behind the journal paywall – let me know if you don’t have access, and I can share directly. However, for the remainder of this blog post, I’d like to describe the TATE model itself (without a paywall) and to encourage reflection, comment and questions.

The TATE model

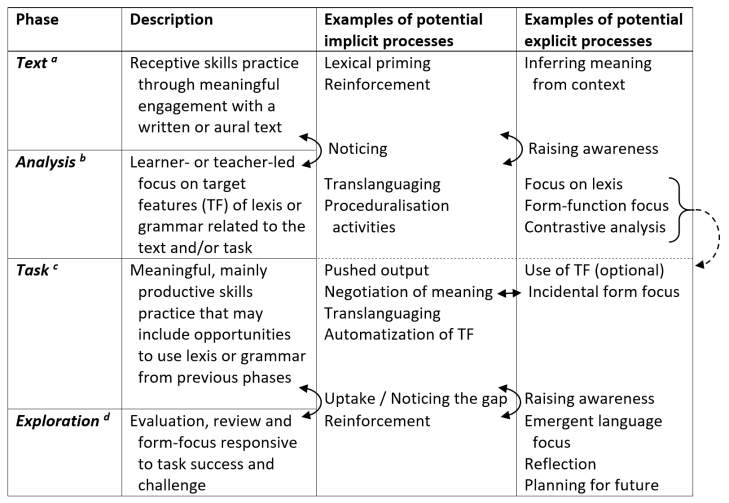

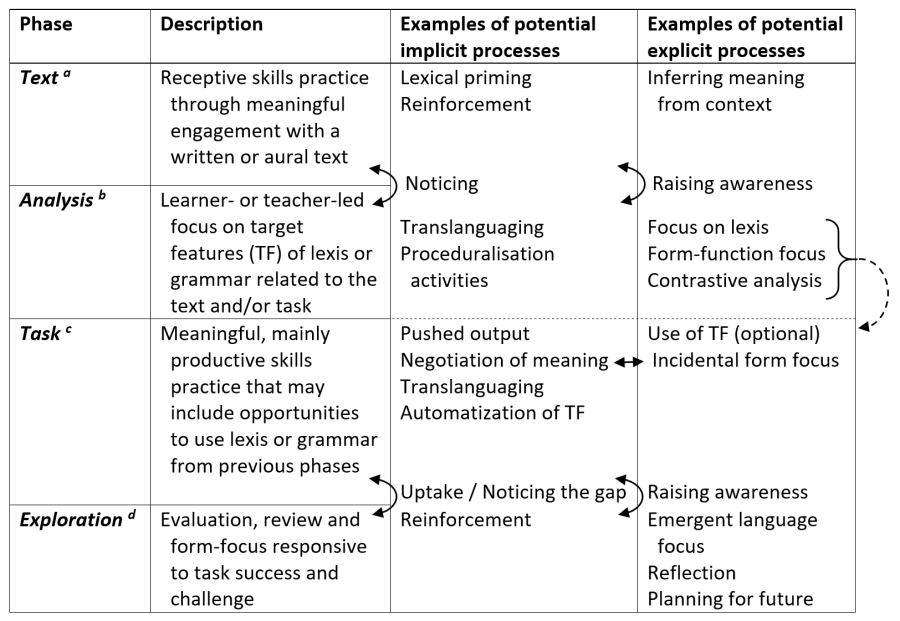

The model is summarised in Figure 1, and described in more detail below. I present it as a task-supported-mainly framework that allows for both implicit and explicit learning processes to occur through the inclusion of meaning-focused tasks and post-task opportunities for ‘exploration’ of a range of areas related to the task itself, such as evaluation, presentation, future planning and a focus on emergent language.

Text

The first phase of the model involves a written or aural text (recorded or live) or texts (as in jigsaw activities), as are often found towards the start of units in ELT coursebooks, and also recommended in some models for TBLT during task preparation (for example, Willis 1996, p. 45). As is common in many ELT textbooks, pre-text preparation activities may involve lexical work or schema-raising, and while-reading/listening activities are envisaged that engage learners primarily with the meaning-content of the text. There is nothing original here – the framework acknowledges the increasing role that the inclusion of such texts is playing in language learning in national secondary curricula and assessment frameworks worldwide, as well as in more academic studies and IT-mediated work environments (as well as global coursebooks), as an opportunity for language input and receptive skills practice.

Analysis

The analysis phase involves analysis of specific features/items of lexis or grammar found in (or related to) the text(s) that may also be useful during the subsequent task phase. It is envisaged to begin with an awareness raising ‘bridge’ task to promote ‘noticing’ of the selected lexical or grammatical features in the text, followed by an attempt to develop learners’ explicit knowledge of said features. The model does not prescribe any approach to analysis, allowing for both learner-oriented approaches, as in discovery-learning (Bruner, 1961), and more direct instruction, consistent with reduced cognitive load theory (Waters, 2015). The analysis phase also suggests (where appropriate) multilingual language exploration, through contrastive analysis with shared other languages (SOLs) in the classroom, or more implicit translanguaging practices that embed target features in a more familiar language during analysis to provide more accessible ‘co-text’ for the target features. Analysis phases may also include activities categorised under ‘practice’ in the PPP model (e.g., spoken drills, cloze exercises, or other activities to facilitate proceduralisation of the declarative knowledge involved; DeKeyser, 2015; Anderson, 2016).

Task

The task phase is envisaged as a meaningful opportunity for extensive productive skills work, written or spoken, and may extend over several lessons during projects. The term ‘task’ was chosen, rather than ‘practice’ to emphasise the importance of meaningful, holistic language use, as discussed above, rather than simply practice of features introduced during analysis. Consistent with TSLT, it would typically provide an opportunity for learners to draw upon the language focus of the analysis phase (lexical or grammatical), although this would not be considered obligatory, and would depend on individual learner differences with regard to readiness for a specific structure, grammatical inferencing ability and aptitude for ‘noticing the gap’ (Ellis, 2019). As well as tasks designed to provide opportunities for the use of grammatical features, due to the dual lexical and grammatical focuses of the TATE framework, tasks that have primarily functional or transactional foci may also be included (i.e. with no specific grammatical focus); on such occasions, the analysis phase may be oriented towards appropriate lexical resources for use during the task (thematically related), or on receptive-only analysis of features of the text, meaning that the model may also include unit cycles consistent with the natural order theory that underpins stronger TBLT models. Language choice during the task will vary depending on context, but, particularly when learners (especially at primary and secondary levels) share resources beyond English, these may naturally figure in such tasks, likely though what I have previously called both ‘partly’ and ‘highly translingual practices’ (Anderson, 2018, p. 28). Responsive focus on form (e.g., correction, clarification requests, etc.) from teacher and/or peers may occur during this phase as appropriate to context, participants and task.

Exploration

The final phase of the model involves post-task exploration of any of a number of areas depending on the nature of the task. Some of these may also involve meaningful language use, constituting ‘meta-tasks’ in so much as they focus on exploration of task performance and its consequences (expanding on Willis’s ‘planning’ and ‘report’ stages; 1996). The phase may include:

- a responsive focus on emergent language, which may include specific focuses on forms used, and corrective feedback where deemed appropriate by the teacher or requested by learners, but also on providing input of alternative lexis, functional exponents and structures appropriate to perceived communicational needs and developmental levels of learners;

- learner-centred presentations, peer-review (for example, of written texts) or publishing (for example, online) of outcomes of tasks or projects when appropriate;

- self-, peer- and teacher evaluation of achievement or performance during the task; how successfully it was completed and reflection on challenges faced in ways that could potentially align with continuous and formative assessment frameworks in mainstream education;

- planning for future learning, such as when a need is perceived for a specific, possibly remedial, language focus prompted by reflection upon task performance – this may be useful, for example, for novice teachers or teachers with lower proficiency in the TL who feel more challenged by the unpredictability of responsive form focus.

The extent to which each or any of these four areas may be the focus of the exploration phase will necessarily be determined by the length of the TATE cycle (compare one-lesson cycles with two-week cycles), the specific syllabus context of the course (compare short, communication-oriented courses and year-long national syllabi involving project work), and context-specific norms and expectations (whether a remedial language focus is deemed appropriate, for example, or whether end of year exams—typically beyond the teacher’s control—test declarative knowledge of aspects of language).

Reflexivity: concerns about my model

One important point that Rod Ellis mentions in his response to my proposal (2020) is the possibility that prior ‘instruction’ (i.e., some kind of explicit language focus) before a task can have a negative impact on the way that students perform the task. Many students may see a task as an opportunity to use the new language (some may want to demonstrate this to the teacher), reducing the degree to which they engage with the task as a more open opportunity for meaningful communication. Within the natural order theory of learning, this is perceived to reduce the likelihood of implicit learning occurring during the task. Typically, complexity, accuracy and fluency are used as measures of ‘quality’ of learner production at such times, and the assumption is that if this ‘quality’ falls, they’re using it as a practice opportunity. This is not necessarily a problem from a skill-acquisition theory perspective – ‘practice makes perfect’ – but it would potentially refute my second assertion above, that even if tasks are used after ‘instruction’, they don’t stop learners from using language meaningfully. Ellis cites one study in support of his position (Ellis, Li & Zhu, 2019; ironically, this study uses a treatment that is consistent with the TATE framework – see Anderson, 2020b), and I cite two that demonstrate that this isn’t necessarily the case (Mochizuki & Ortega, 2008; Sangarun, 2005), which is the point I was making (note the ‘can’ in this quote):

…even when used within a synthetic grammar curriculum, tasks can retain the primarily meaningful communication and holistic language use that allows for implicit learning to occur alongside the explicit practice of specific structures. (Anderson, 2020a, p. 3)

Of course, as experienced teachers know, the reality is that this will depend on a number of factors, such as the nature of the task itself, learner engagement, and how the teacher sets up the task, to name a few. We both agree that more research is needed in this area to understand what is happening. My personal feeling is that qualitative research would be particularly useful among the more experimental trials, interviewing students to understand what they felt they were doing in such instances and why (a potential PhD/MA study, perhaps?).

Two other concerns that Ellis doesn’t mention relate to the very challenge we both take on, that of trying to combine approaches that are based on these rather different theories of learning. From one side, looking at Figure 1, I wonder if it isn’t just a mash up of stuff I like, or feel empathy towards, and from the other, the fact that I present my framework as a prescriptive sequence (T>A>T>E) could cause it to become a straightjacket, constraining creativity on the part of the teacher, and lowering learner engagement, as arguably happened with PPP in the 1980s (Anderson, 2017b). Describing ‘CAP(E)’ as a thing that’s out there, a ‘social fact’ of sorts (Freeman, 2016), is one thing, but proposing TATE as a framework for curriculum planning requires a potentially dangerous leap of faith.

Déjà vu, or poo-poo?

If the model looks familiar – like one of your own lessons or units of study, for example, this blog post may have offered you little new, except confirmation that someone else shares a similar perspective. I have always agreed with Shulman (2004) that there is a ‘wisdom of practice’ in what many of us have learnt to do through experience, and I believe that this model reflects that – curriculum design from a Schönian perspective, of sorts; one that values experiential expertise, and seeks to understand it, rather than the technical rationality of applied science (e.g., SLA research) that Schön was so critical of (1983). And I believe that, in the two papers (2020a, 2020b), I also make the case for such practice from a research-informed perspective – I see it as no less consistent with the evidence than Ellis’s curricular framework, and certainly more aware of research beyond the often rather narrow focus on the acquisition of grammar for spoken use underpinning much of the cognitive SLA literature (Anderson, 2020b) – hence the title of my response to… his response… to my response to his framework.

And if it looks rather different to what you do, I do not wish to imply that yours is not an equally informed practice – a sizeable chunk of my teaching doesn’t ‘TATE’, either! But, as I caution at the end of the first of these papers, the framework “is not offered as a universal model” (2020a, p. 9), and will not be appropriate in all contexts, nor useful for all practitioners. Reflections, comments and critique are welcome below.

References

Anderson, J. (2016). Why practice makes perfect sense: The past, present and potential future of the PPP paradigm in language teacher education. ELTED, 19, 14-22. Here.

Anderson, J. (2017a). Context, analysis and practice. IATEFL Voices, 256, 4-5. Here.

Anderson, J. (2017b). A potted history of PPP with the help of ELT Journal. ELT Journal, 71/2, 218-227. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/ccw055

Anderson, J. (2018). Reimagining English language learners from a translingual perspective. ELT Journal, 72/1, 26–36. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/ccx029

Anderson, J. (2020a). The TATE model: a curriculum design framework for language teaching. ELT Journal. Advance access: https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/ccaa005

Anderson, J. (2020b). A response to Ellis: The dangers of a narrowly focused SLA canon. ELT Journal. Advance access: https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/ccaa016

Andon, N. & Norrington-Davies, D. (2019). How do experienced teachers deal with emergent language? Paper presented at IATEFL Conference, Liverpool, UK.

Bruner, J. S. (1961). The act of discovery. Harvard Educational Review. 31/1, 21–32.

DeKeyser, R. (2015). Skill acquisition theory. In B. VanPatten and J. Williams (Eds.), Theories in Second Language Acquisition: An Introduction (Second edition). New York: Routledge.

Elgort, I. & Nation, P. (2010). Vocabulary learning in a second language: familiar answers to new questions. In P. Seedhouse, S. Walsh and C. Jenks (Eds.), Conceptualising ‘Learning’ in Applied Linguistics. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Ellis, R. (2003). Task-based language learning and teaching. Oxford: OUP.

Ellis, R. (2019). Towards a modular language curriculum for using tasks. Language Teaching Research, 23/4, 454–75. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362168818765315

Ellis, R. (2020). In defence of a modular curriculum for tasks. ELT Journal. Advance access: https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/ccaa015

Ellis, R., Li, S. & Zhu, Y. (2019). The effects of pre-task explicit instruction on the performance of a focused task. System, 80, 38–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2018.10.004

Freeman, D. (2016). Educating second language teachers. Oxford: OUP.

Harmer, J. (1998). How English works. Harlow: Longman.

Lewis, M. (1993). The Lexical Approach: The State of ELT and a Way Forward. Hove: Language Teaching Publications.

Long, M. (2015). Second Language Acquisition and Task-Based Language Teaching. Chichester: Wiley Blackwell.

Mochizuki, N. & Ortega, L. (2008). Balancing communication and grammar in beginning-level foreign language classrooms: a study of guided planning and relativization. Language Teaching Research, 12/1, 11–37. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F1362168807084492

Sangarun, J. (2005). The effects of focusing on meaning and form in strategic planning. In R. Ellis (Ed.). Planning and task performance in a second language. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Nation, P. (1996). The four strands of a language course. TESOL in Context, 6/2, 7-12.

Schön, D. (1983). The reflective practitioner: How professionals think in action. New York: Basic Books.

Shulman L. S. (2004). The wisdom of practice: Essays on teaching, learning and learning to teach. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Waters, A. (2015). Cognitive architecture and the learning of language knowledge. System, 53, 141–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2015.07.004

Willis, J. (1996). 1996. A Framework for task-based learning. Harlow: Longman.

Thank you for giving this explanation of your model outside the paywall! Not to be too glib, I think a huge factor in its favour is that it is neat and pronounceable (TBLT? TSLT?!) as well as memorable. I don’t think it matters too much that it reflects what is already being done in many language classrooms, future MA TESOL lecturers and teachers will thank you for it as something to show that ELT is moving on and developing tried and trusted frameworks, synthesising all that is good in what went before.

LikeLike

Thanks Tilly!

LikeLike