Jason Anderson and Jaber Kamali

We think of life almost as one thinks of a work of fiction: we have one or many plot lines; we are a character in our own stories; others become characters in our stories; we live our stories in cultural and social settings that shape the stories we live and tell; we are gendered characters; we are characters in other’s stories. Thinking of life as a story is a powerful way to imagine who we are, where we have been, and where we are going. (Connelly & Clandinin, 1994, p. 149)

The above reflections come from the writings of Michael Connelly and Jean Clandinin, probably the first two researchers who attempted to understand teachers from the perspective of narrative. In their work, Connelly and Clandinin document the profound importance of stories not just in researchers’ understandings of teachers, but also in teacher learning. More recently, researchers in language teaching, including Karen Johnson (e.g. Johnson & Golombek, 2002) and Gary Barkhuizen (e.g. 2016b, 2017) have demonstrated the importance of narrative, linking this to how we understand ourselves, our identities and our social environments. Indeed, it has been argued that “storythinking”, as Fletcher calls it (2023), offers an alternative way to understand the world (at least our experience of it) to the logical thinking tradition that has dominated Western thought since Aristotle.

If this is true, it follows that there may be ways not just for researchers to understand teachers through stories, but for us, as teachers, to understand ourselves – our identities, beliefs, values and practices through stories. This was our hypothesis when we embarked on a research project together to investigate the possibility of introducing a more narrative approach to understanding our experiences on a daily basis – the lessons we teach and how our reflections around these lessons help us to learn.

Adding a narrative element to lesson observation

Our focus of interest in our exploratory discussions together was the lesson observation procedure and its potential as a tool for teacher learning, not simply teacher evaluation. As Mario Rinvolucri long ago observed (1998), one of the fundamental problems with lesson observation is (ironically) the so-called observer effect. Because the observer, through their very presence, changes the way that we plan and teach these observed lessons, so much of what they see and then provide feedback on isn’t actually ‘real’ or relevant to our day-to-day practice – it’s an artifice created by the observation event itself. As a result, as one of the participants in our research put it:

I don’t value, when I get the feedback, I don’t tend to read it. It’s like a phobia seeing it. (Ahmed, interview)

What Rinvolucri proposed, paradoxically, was “unseen observation”, a process in which the observer provides the necessary support around the lesson (e.g. reflective conversations before and after the lesson), but trusts the teacher to self-observe the lesson alone.* Both Phil Quirke (1996) and Matt O’Leary (2022) have built on Rinvolucri’s work, describing similar procedures for providing support during what O’Leary calls “formative”, rather than “summative”, lesson observation. We felt that O’Leary’s framework for unseen observation was promising, but have also been inspired by recent research on teacher autoethnography (e.g. Kamali, 2023, 2024) and storying (e.g. Barkhuizen, 2016a; Dikilitaş et al., 2025). Jaber’s initial idea was to combine critical autoethnography with unseen observation. Expanding on this, we wondered whether including a stronger narrative element in the lesson observation process would enable teachers to explore the procedure more deeply and meaningfully. This will enable them to identify not simply ‘what’ happened in the lesson itself, but where exactly the ‘what’ came from, why it happened and what impact it had, both on our learners and us – aspects of our professional identity and values. In doing so, we felt, this narrative process would enable us to identify and explore the “core qualities” that are central to our theories and practices (Korthagen, 2017), thereby leading to the kind of deeper reflection that, Schön (1983) argued, could be transformative and sustained. Korthagen, calls this “core reflection” (2017, p. 395) in his Professional Development 3.0 framework.

Narrative self-observation

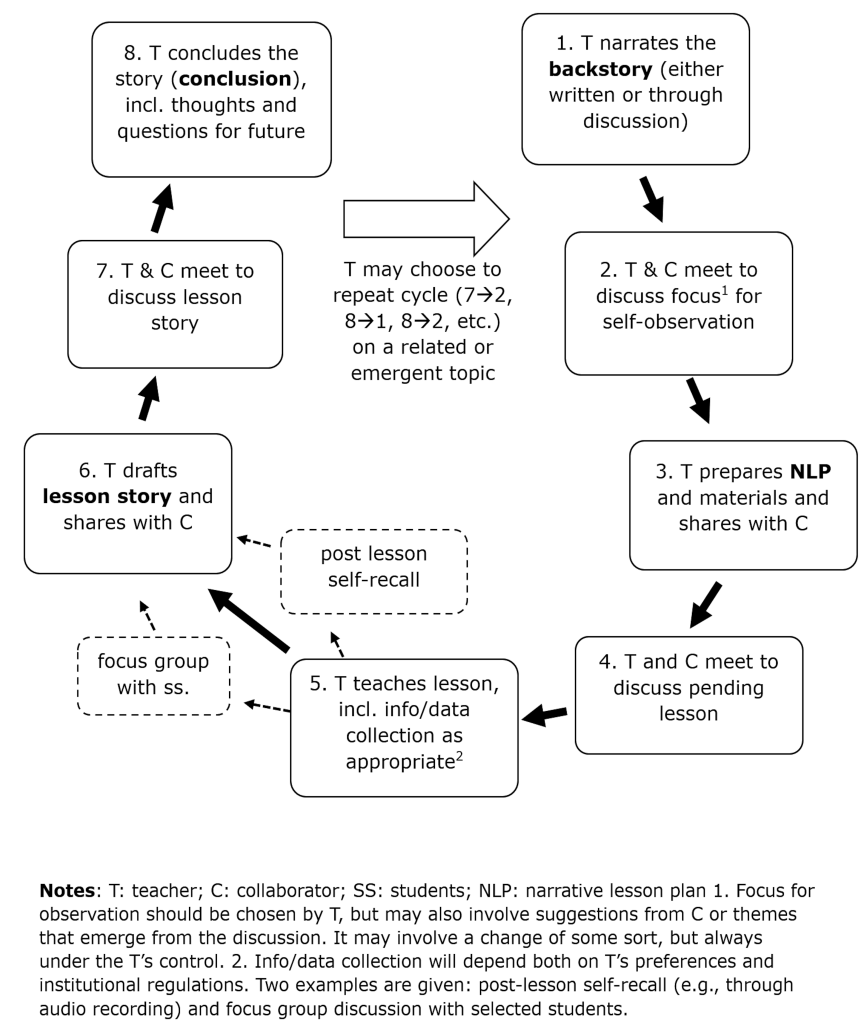

We decided to call the process we developed “narrative self-observation”, building on O’Leary’s (2022) suggested cycle for unseen observation to create a framework for teacher research and development – see Figure 1 (from Kamali & Anderson, 2025). We also created some supplementary resources to enable teachers and their collaborators (following O’Leary, we prefer this word to “observer”) to conduct the process of narrative self-observation (henceforth, NSO) – see here.

NSO follows eight stages, yet it’s not a rigid checklist. Think of it more like a cycle. Each round of NSO can naturally lead to the next, as new questions or stories emerge. It can be narrated in written form or spoken form (e.g., through audio recording). Meetings can be face-to-face or online. The process starts in Stage 1 with the teacher sharing their “backstory”: who they are, what their class is like, and the challenges or puzzles they’d like to explore. In Stage 2, with the support of the collaborator, they discuss the backstory and choose an observation focus. This could be a puzzle, a challenge, or an area of interest that the teacher wants to explore in their classroom. In stage 3 the teacher narrates their lesson plan and shares this with the collaborator. This can be any type of lesson plan, but in our work we have experimented with what we call “narrative lesson plans” (see below), in which the teacher describes the intended lesson and the rationale behind it in continuous text, rather than the abbreviated form typical of most lesson plans. Stage 4 involves a brief second meeting to explore how the chosen focus will be investigated during Stage 5, the lesson. Teachers in our study (see below), with learner permission, have used a range of means including audio-recorded lessons, live written notes during the lesson and self-recall immediately after the lesson to help them. Other means might include a focus group meeting with several trusted students or images of board work or student work. But rather than seeing this as formal “data collection”, we encourage teachers to use whatever feels natural to them at this stage. The teacher then drafts a lesson story, perhaps a day or two after the lesson, and shares with the collaborator (Stage 6). This isn’t a report card on the class (or the teacher!), but a narrative reflection on key moments, feelings, and discoveries. It naturally leads to a final meeting in which they discuss the lesson (Stage 7), focusing primarily on the chosen focus, reflecting both on what was learnt and what might come next. The final step is wrapping up the lesson story (Stage 8), sometimes revising it after further thought, and deciding whether to begin another cycle.

In the full article we link this cycle to the theories of learning that underpin it (pp. 6-7). It borrows from action research and experiential learning frameworks, but it’s deliberately light on data collection so it stays practical and teacher-friendly. The framework is a proposal only, open to adaptation as required for different contexts and purposes. So, if you’re interested, feel free to adapt it to your own needs and let us know how it goes. More recent uses of the framework have, for example, involved larger groups of teachers at certain points in the process, and spoken, rather than written, narration. Shaun Wilden has also experimented with using Generative AI (see here) as the collaborator, finding that it helps to hold a non-judgemental mirror to his practice, and certainly serves as an additional tool for data collection during the observation (data protection issues aside).

Narrative lesson planning

An interesting, yet unexpected, additional output of the project was the discovery of what we have called “narrative lesson planning” (Anderson & Kamali, 2025), as a means to facilitate a more joined up, formative way of planning lessons. It occurred to us that current lesson plans are designed around the (practical) needs of the observer, rather than the developmental needs of the teacher. As a result, lesson plans actually end up being abbreviated, ‘boxed’ summaries of a much more complex, non-linear process (Clarke & Peterson, 1986) that is not revealed the observer. Yet, as our research has found (e.g., Oncevska-Ager & Anderson, 2025), not only is planning an essential part of teacher learning, it’s also essential to understanding teacher decision-making and the assumptions underpinning it. Thus, a lesson plan that includes some of our background thinking (particularly our reasons or rationales), expressed as an honest stream-of-thought process (either written or spoken), reveals so much about our thinking that can enable both the observer/collaborator, and us, as self-observers, to understand this crucial phase of our practice. In our article in Modern English Teacher, we suggest a number of ways of writing a narrative lesson plan, including in written or spoken form, and also acknowledge the earlier work of Marie Doyle (see Doyle & Holm, 1998) on “story lesson plans”, which her team found to be a useful tool in preservice teacher education (click here for guidelines and if you can’t access the article 😉 – drop us a message).

Where’s the evidence that this works?

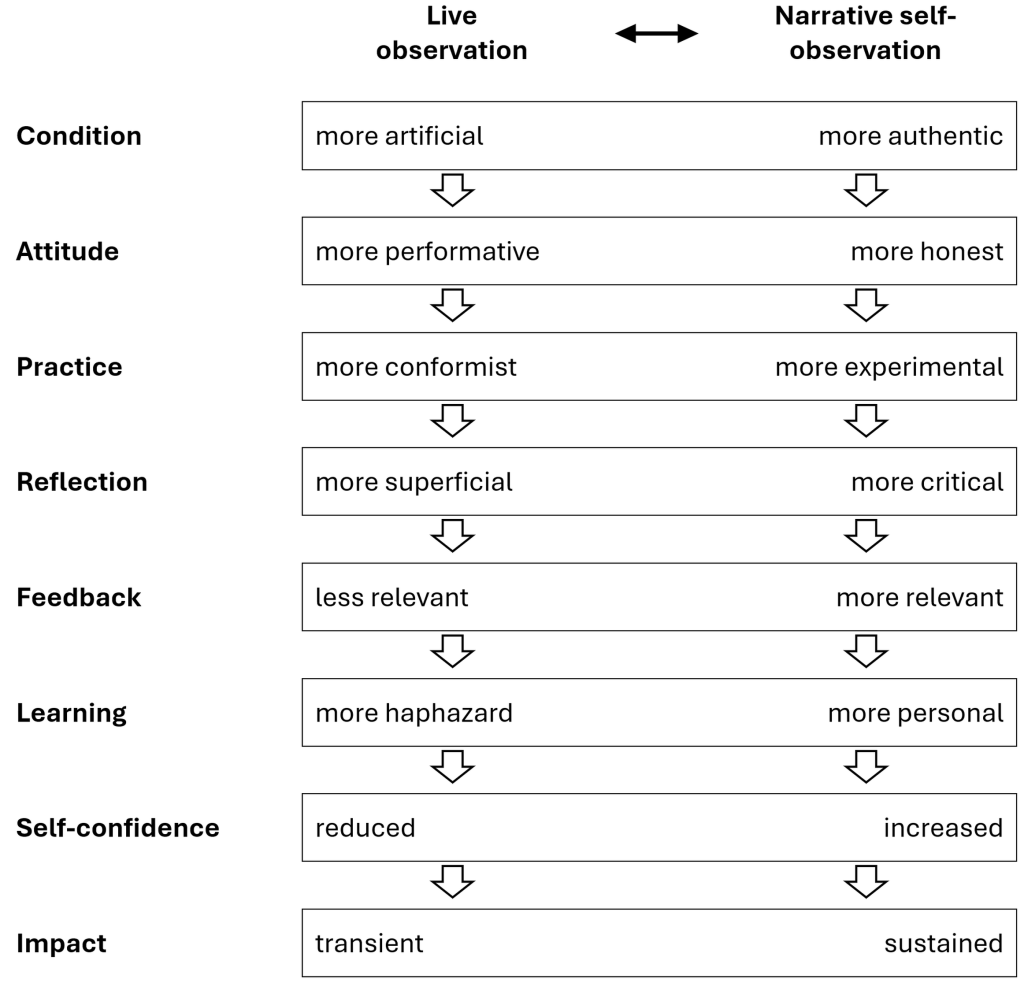

We have conducted a small-scale, proof-of-principle study with three teachers to investigate the impact of narrative self-observation (Kamali & Anderson, 2025), both from the perspective of teacher professional learning as well as their deeper reflection and identity development. We found that NSO offered the teachers a more authentic and empowering experience when compared with live observation. All felt that it reduced the stress and negative impact that they had experienced in “traditional” live observations, which one called “robotic,” and another openly admitting he avoided reading the “feedback” from (see quote above). In NSO, by contrast, lessons felt more “honest” and “healthier”, afforded greater freedom to experiment and provided more concrete insights into their classroom practice that they felt were more sustainable. As one explained: “The advantage of NSO is that the teacher has more chance to learn from trial and error” (Mina, interview**). This freedom led to insights of real, practical value. Mina realised that she often made rushed decisions that “hurt” her lessons and Ahmed discovered “great value in deviation”, which can nonetheless be planned for (see Anderson, 2015). Hande, who had been demotivated by past live observations, found comfort in audio-recording her lessons: it gave her “solid proof” of her strengths and areas to grow. On a deeper level all three teachers felt that conducting narrative self-observation enabled them to be more honest with themselves, reflecting more deeply and feeling greater empowerment as a result. One of them summed up the process well in her own lesson story as follows:

This experience has been an eye-opener for me. It has allowed me to realise the power of systematic self-observation and how useful it can be alongside traditional observation. It has also made it possible for me to understand the power of looking back at my journey as an English teacher, how I started, where I am now and where I can go in the future. This vision becomes much clearer by documenting it. (Mina, Story)

While the teachers all agreed that NSO shouldn’t replace live observation, they all saw its long-term potential. As Hande summed up: “I was able to customise my professional development” – imagine if every teacher had that chance!

Full details are reported in the NSO article itself, where the following figure is also presented as a means to contrast some of the shortcomings of live observation with the alternative (best case) opportunities provided by NSO.

An invitation to experiment

Just as NSO is itself a framework for experimentation in the classroom, we offer these two tools (the NSO cycle itself and narrative lesson planning) as works in progress for colleagues to try out. We encourage teacher educators (including trainers, line managers and mentors) to adapt them – however they see fit – for their own contexts, and also encourage teachers interested in trying out a new type of self-study research to find a collaborator and try out NSO in their classrooms. We believe that both the observation cycle and the lesson planning proposals can serve as powerful tools to explore narratives in our own learning as teachers!

Please share your questions, thoughts and critique below.

References

Anderson, J. (2015). Affordance, learning opportunities and the lesson plan pro forma. ELT Journal, 69(3), 228-238. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/ccv008

Anderson, J. & Kamali, J. (2025). Narrative Lesson Planning. Modern English Teacher, 34(5), 64-67.

Barkhuizen, G. (2016a). A short story approach to analyzing teacher (imagined) identities over time. TESOL Quarterly, 50(3), 655-683. https://doi.org/10.1002/tesq.311

Barkhuizen, G. (2016b). Narrative approaches to exploring language, identity and power in language teacher education. RELC Journal, 47(1), 25-42. https://doi.org/10.1177/0033688216631222

Barkhuizen, G. (2017). Language teacher identity research: An introduction. In G. Barkhuizen (Ed.) Reflections on language teacher identity research (pp. 1-11). Routledge.

Clark, C. M. & Peterson, P. L. (1986). Teachers’ thought processes. In M. C. Wittrock (Ed.), Handbook of research on teaching (3rd ed.) (pp. 255-296). Macmillan.

Connelly, F. M., & Clandinin, D. J. (1994). Telling teaching stories. Teacher Education Quarterly, 21(1), 145-158.

Dikilitaş, K., Eryılmaz, R., Mukherjee, K., Serra, M., & Anderson, J. (2025). The emergence and significance of meta-identity in the professional development of experienced teacher-researchers. Teacher Development (Advance online access). https://doi.org/10.1080/13664530.2025.2515916

Doyle, M. and Holm, D.T., 1998. Instructional planning through stories: Rethinking the traditional lesson plan. Teacher education quarterly, 25(3), 69-83.

Fletcher, A. (2023). Storythinking: The new science of narrative intelligence. Columbia University Press.

Johnson, K. E. & Golombek, P. R. (2002). Inquiry into experience: teachers’ personal and professional growth. In K. E. Johnson & P. R. Golombek (Eds.) Teachers’ narrative inquiry as professional development (pp. 1-14). Cambridge University Press.

Kamali, J. (2023). Metamorphosis of a teacher educator: A journey towards a more critical self. Journal of Applied Learning and Teaching, 6(2), 252–259.

Kamali, J. (2024). An ecological inquiry into the identity formation of a novice TESOL research mentor: Critical autoethnographic narratives in focus. Language Teaching Research, 13621688241251953. https://doi.org/10.1177/13621688241251953

Kamali, J. & Anderson, J. (2025). Narrative self-observation: A new framework for teacher professional development and identity research. European Journal of Teacher Education (Advanced Online Access). https://doi.org/10.1080/02619768.2025.2563113

Korthagen, F. (2017). Inconvenient truths about teacher learning: Towards professional development 3.0. Teachers and teaching, 23(4), 387-405. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2016.1211523

O’Leary, M. (2022). Rethinking teachers’ professional learning through unseen observation. Professional Development in Education, 1-14. https://doi.org/10.1080/19415257.2012.693119

Ončevska Ager, E., & Anderson, J. (2025). Affordance-based lesson planning in pre-service teacher education. ELT Journal, 79(1), 1-11. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/ccae048

Quirke, P., 1996. Using unseen observations for an in-service teacher development programme. The teacher trainer, 10 (1), 18-20.

Rinvolucri, M. (1988). A role-switching exercise in teacher training. Modern English Teacher, 15(4), 20-25.

Rinvolucri, M. (1998). Why threaten the teacher with observation? Perspectives, 98(8), 15-18.

Schon, D. (1983). The reflective practitioner: How professionals think in action. Basic Books.

Wilden, S. (2025). From Gandalf to GPT: What My AI Mentor Has Shown Me (So Far) [Blog Post]. Shaun Wilden. https://wildeshaun.substack.com/p/from-gandalf-to-gpt-what-my-ai-mentor

Notes

*While Phil Quirke is confident that ‘unseen observation’ does come, initially, from Rinvolucri’s treasure chest of creativity (P. Quirke, pers. comm.), we are still to track down the exact article in which he introduces the term. The piece cited by Quirk and O’Leary (Rinvolucri, 1988) doesn’t mention it. Do let us know if you know of, or have it!

**Pseudonyms used throughout.